ART WRITING

INTERVIEWS WITH ARTISTS

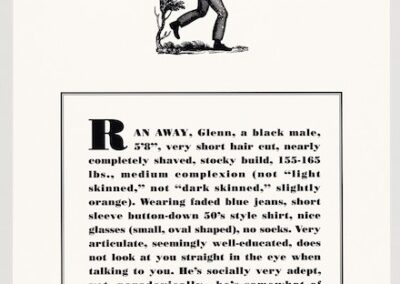

GLENN LIGON

Runaways (detail), 1993. Suite of 10 lithographs, 16 x 12 inches. Published by Max Protetch; Printed By Petersburg Press. Photo: Robert Gerhardt and Denis Y. Sus. © Glenn LigonCourtesy of artist, Hauser & Wirth, New York, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Thomas Dane Gallery, London and Chantal Crousel, Paris.

GLENN LIGON

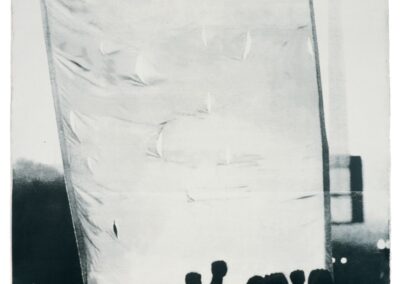

We’re Black and Strong (I), 1996. Silkscreen ink and gesso on unstretched canvas. 120 x 84 inches. Collection of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art SFMOMA. © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, New York, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Thomas Dane Gallery, London and Chantal Crousel, Paris.

GLENN LIGON

Installation view, Glenn Ligon. First Contact, at Hauser & Wirth Zurich, Limmatstrasse, until 23 December 2021. © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Jon Etter

GLENN LIGON

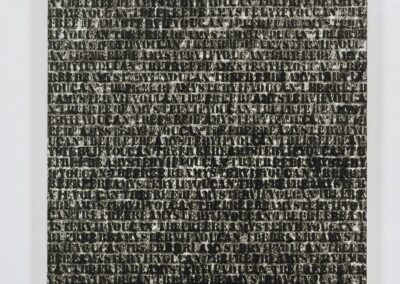

Canary (For Rita Dove), 1991. Oil on wood. 80 x 30 inches. © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, New York, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Thomas Dane Gallery, London and Chantal Crousel, Paris.

GLENN LIGON

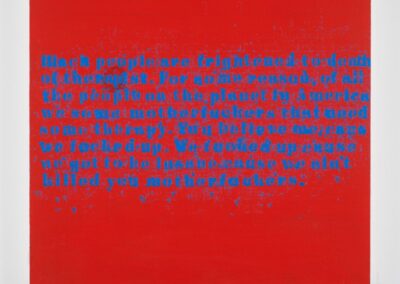

Therapy #2, 2004. Oil stick and acrylic on canvas. 30 x 30 in. Photo: Farzad Owrang. © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, New York, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Thomas Dane Gallery, London and Chantal Crousel, Paris.

GLENN LIGON

A Small Band, 2015.Neon, paint, and metal support, 3 components: “blues” 74.75 x 231 inches; “blood” 74.75 x 231.5 inches; “bruise” 74.75 x 264.75 inches; approx. 74.75 x 797.5 inches; Collection of Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. Photo: Roberto Marossi. © Glenn Ligon. Courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, New York, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Thomas Dane Gallery, London and Chantal Crousel, Paris.

Glenn Ligon with Raphael Rubinstein

“There are many ways to make a painting, but in some ways, I’m very committed to an old-fashioned way of work, just me in the studio making a thing.”

Glenn Ligon’s practice is so multi-faceted that separate interviews could be devoted to his curating and to his art writing, as well as to the most obvious topic of his art-making. Recently, Ligon has also directly addressed online misuse of his work. While we touched on those topics, this conversation, which was conducted on Zoom the month before his November exhibition of new work at Hauser & Wirth in New York (this will be his first New York show with the gallery), focuses on his art, especially his recent mural-scaled paintings using the entire text of James Baldwin’s 1953 essay “A Stranger in the Village.” For much of 2021, anyone passing by the New Museum on the Bowery would have seen Ligon’s 2015 neon sculpture A Small Band on the museum’s façade. Originally created for the 2015 Venice Biennale, the work was re-installed on the New Museum as part of Grief and Grievance: Art and Mourning in America, an exhibition conceived by Okwui Enwezor. After Enwezor’s death in 2019, Ligon, calling on his own extensive curatorial experience, was among those who helped the museum to realize Enwezor’s powerful exhibition. “Blues blood bruise,” the three words that make up A Small Band, derive from a statement by Daniel Hamm, a Black New York City teenager who was arrested and brutally beaten by the police in 1964. As is true with all of Ligon’s work, this glowing memorial displays a concrete engagement with history, a sensitivity to the slipperiness of language and a presence that combines immediate visual impact with a slower unfolding of complex content. And, it almost goes without saying though it must always be said, a witnessing and critique of the racism that continues to plague our nation.

Raphael Rubinstein (Rail): It was almost 30 years ago that I wrote a piece on you for Art News. You were doing the Runaways portfolio, inspired by 19th century broadsides seeking the return of runaway slaves. It’s a shock to realize that much time has gone by.

Glenn Ligon: I think those pieces were done for a show at the Hirshhorn in 1993. Nice to talk to you again.

Rail: After a slight hiatus! [Laughter] I’d like to start by asking if you’ve seen the Jasper Johns show at the Whitney. In the course of preparing for this interview—reading and re-reading a lot of what’s been written about your work—I was struck by Hilton Als’s observation that Johns and James Baldwin were your main influences and how different they are. Johns, with his cold surfaces, is saying to the viewer, “stay away,” where Baldwin is just the opposite. The “I” is very present, he’s welcoming you, opening up his heart.

Ligon: I’ve only seen the Johns show in the context of an opening, but one of my initial thoughts is that I am always interested in how Johns has explored the same kinds of motifs over years and decades, teasing out new material in the same way that someone like Morandi teased dozens and dozens of canvases from arrangements of the same bottles or vases on a table. Johns is also interesting to me because of the technical stuff: the variation of surfaces, how he goes from medium to medium, how rigorous his investigations are. Contrary to what Hilton has said, I don’t know if Johns is a main influence on me, but as for that formulation between Johns and Baldwin, it’s true that Baldwin was very emotionally and personally invested in his writing. As you said, his “I” is always present in his essays. So I’m sort of in between. Most of the text work that I’ve done is quotation. There’s an “I” in it but it’s not mine. Maybe I’m channeling Johns in some way because there’s a distance between me as an artist and the viewer. But those words I use get read very autobiographically, and they’re often from sources that have a particular kind of political resonance or are dealing with some social issues, so they seem hot in the way that Johns seems cool.

Rail: In terms of influences, it looks to me as if the appropriation artists of the mid-1980s would have been a much greater and more direct influence on your work. Even though your work doesn’t look at all like Richard Prince or Sherrie Levine, like them you also make your work out of pre-existing images or language by transferring material from one context to another. But there’s a crucial difference. With Prince or Levine, the denial of artistic labor in re-photography is part of their post-studio aesthetic position, a way to say “we are not artists who get our hands dirty.” But your version of appropriation has always involved extensive labor in a studio.

Ligon: Right. But I also think the source material they use circulates in the world in a different way than the source material that I choose. When I started using James Baldwin, nobody was talking about Baldwin in the way that everybody is talking about him now. The same with Zora Neale Hurston and Ralph Ellison. Those texts circulated in a very different way than an image drawn from advertising or even from Dorothea Lange or Walker Evans. (In the case of Sherrie Levine.) I also think that I am, in the end, a painter. There are many ways to make a painting, but in some ways, I’m very committed to a very old-fashioned way of work, just me in the studio making a thing, as opposed to running a vacuum press or phoning my silk-screener or whatever. I do those things, but primarily I consider myself a maker.

Rail: Who is mostly alone in his studio.

Ligon: I’m doing a talk with Julie Mehretu in a couple of days and I’ve been looking at a film by Tacita Dean that was made in Julie’s studio, and also some footage that was shot for the arts program ART21 and it was shocking to me to see how many people Julie has to engage with to make her work. I know there are plenty of moments where it’s just her and the canvas but in these films there are dozens of people in the studio, which is the only way that work can be made because of its scale and complexity. But that is absolutely not my process. That’s a nightmare scenario to me. I love Julie’s work and that’s her personality, she has a vision for her work that operates almost in a public sphere: in the film there’s literally a dozen people standing around watching her make her work. I’ve never been able to think of my production in that kind of way.

Rail: Another comment that struck me was where Darby English describes writing a paper for Douglas Crimp at the University of Rochester in the mid-1990s. He read through everything that had been written about you up until that point and he was, I think he uses the word “flabbergasted,” by the fact that there was no discussion of the work in formal terms, no acknowledgement of its engagement with its textures and materiality, its status as painting. Instead it was all generalizations, all about the subject matter, the supposed content, with a very narrow view or understanding of what content is. Was this something that you were aware of in the responses to your work? If so, has anything changed? Do you feel that writing on your paintings has done enough to acknowledge their formal properties?

Ligon: No, but in the era that Darby is referring to, the writing was filtered through the lens of multiculturalism, not just for me, but around the work of artists of color in general. The focus was on the politics of the work, never on how the work was made. So yeah, that’s always been an issue, but I think any artist has to seek out those writers and critics who are attentive to all the things the work is about, not just one of the things that the work is about. Darby has certainly been that kind of critic for me.

Rail: Some artists just ignore or don’t engage with the response to their work. Then there are those who are very involved in its reception. Adrian Piper would be someone who is extremely attentive to how her work is written about. I think you have been, too. Somewhere, maybe in your Flash Artconversation with Adam Pendleton, you say you feel like you have to be “vigilant” about the art criticism that your work provokes. You also say that this vigilance can be a burden. Do you feel that artists need to pay attention to what happens once the work has left the studio?

Ligon: Well, I find sometimes that the writing about the work is like a game of telephone; people go back to the same sources, but they misunderstand them, and then they write something and that gets misunderstood. Also, things that you said 20 years ago become gospel, as if one never changes one’s mind about one’s own work. I remember Yvonne Rainer saying when I was at the Whitney Museum program that artists sometimes have to make a critical discourse around their work, that you can’t rely on others to do it for you. I think that continues to be true in some sense. I have also written about other artists—usually on assignment. It’s not something I do in my leisure time. [Laughs] It can be a good way to think about someone’s work because you run up against your own assumptions. When you actually have put pen to paper, you realize, “oh, there’s much more here that I need to think through.” That’s harder than just stating the shorthand version of “Jasper Johns is X,” or “Julie Mehretu is X.”

Rail: As a writer myself, I know very well how that works! [Laughter]. I was struck by your long 2004 Artforum article on David Hammons (“Black Light: David Hammons and the Poetics of Emptiness”). It’s rare to see such a substantial piece of criticism by one artist on another. As well as writing on art, you have also curated quite a few exhibitions. You are almost kind of a “total service artist,” to borrow the term that Diedrich Diederichsen applied to Martin Kippenberger, who thought that being an artist meant you should take responsibility for every aspect of your career. For each one of his shows, Kippenberger would design a poster, an announcement, an ad, and make a speech at the opening. He said he couldn’t understand why other artists didn’t want to get involved with any of these supposedly ancillary, supplementary things.

Ligon: It’s interesting to think about Kippenberger, though I feel with him it was all a bit of a performance. I find when I’m doing these things, it’s out of necessity. Who else is going to do it? Toni Morrison says you have to write the novels you want to read, so sometimes I felt like okay, well, I have to. . .

Rail: Curate the shows you want to see?

Ligon: Yes. When I curated a show at the Pulitzer Arts Foundation in St. Louis in 2017, it was organized around an Ellsworth Kelly wall relief called Blue Black. Initially, the exhibition was meant to be a solo show of my work, but when I went to do the site visit I said, “You could organize a whole curatorial project around those two colors in the Ellsworth Kelly, but surely somebody must have done that already.” They said, “No, nobody’s done that.” And I thought, well, that’s more interesting to me than to just plop some of my work here. So that project came about from an admiration for Kelly’s work, and a kind of perverse notion of using such charged colors in an artwork in an American context. You could start with Louis Armstrong’s “(What Did I Do To Be So) Black and Blue” and end with David Hammons’s Concerto in Black and Blue. Surely that would be interesting in St. Louis. I can’t imagine Ellsworth Kelly would know what the hell I was talking about, because that wasn’t what his work was about.

Rail: Well, isn’t the importance of a work of art connected to how many different contexts it can be placed in, how many different interpretations it can acquire, how multifaceted its meaning is? Rather than being an example of one particular moment in time, or one style or movement or historical episode, it transcends its initial context. For instance, I was thinking about your “Million Man March” series from the mid ’90s, and how we look at that now, in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests, in the wake of the January 6 insurrection. Another work that I think has changed its meaning is the work you did about the Central Park Five in the early ’90s. It’s impossible, especially now, to separate that from Donald Trump, who famously took out ads in all the New York newspapers calling for the death penalty. That work has, sadly, taken on a new relevance.

Ligon: It’s interesting to me that works which respond to a particular moment are also responding in some ways to the repetition of that moment. So, in terms of the Million Man March, one of the things that struck me in looking at images of this march organized by Louis Farrakhan on the Mall in Washington, DC, the symbolic heart of our democracy, was, “Oh, we’ve done this before!” Black people gather every 20 or 30 years at heart of this nation to assert our presence here. But how strange that is, since we’ve been here since the beginning, or even before it was this thing called the United States of America. So why the need to assert our presence in these spaces over and over again? It’s doomed to failure, because we keep having to do it. But you’re right, that work or the work around the Central Park Jogger case takes on a different resonance because Donald Trump, who is just a crazy pseudo-billionaire real estate developer with right-wing views, becomes the President and has the power to enact his every odious whim. The work does take on a different resonance. I’m interested in the moment this work was being produced, the particularities of that moment, and I’m also interested in its historical repetition. I’ll be seeing these things happen over and over again. Someone asked me in an interview about the specificity of this moment, Black Lives Matter and George Floyd and Ahmaud Arbery and Breonna Taylor, and I just have to say that as long as we live in a culture based on white supremacy: there’s always going to be a Breonna Taylor, there’s always going to be a George Floyd. These things don’t end.

Rail: And, of course, repetition is so central to your work. Although it hasn’t opened yet, I know that your Hauser and Wirth show will include a painting that has, for the first time, the full text of Baldwin’s essay “A Stranger in the Village,” a text you’ve been working with in fragments for decades. What is it that keeps bringing you back to that particular text? And what is the difference between selecting a fragment and painting the entire essay? Basically, you’re publishing Baldwin’s essay in edition of one.

Ligon: Right! That essay keeps rewarding me. I read it for the first time in college in an African American literature class that I took with Robert O’Meally. I keep returning to it because it’s so panoramic. In the space of 10 pages or so Baldwin is trying to deal with his own relationship to these Swiss villagers that he finds himself living among in the early 1950s. Plus he’s thinking about Europe’s relationship to its colonies in Africa. And he’s thinking about his relationship to European history and culture. He’s thinking about his exile. He’s moved to Europe to have a break from American racism, to “ease the bite of it,” as Billy Strayhorn said. All of these things are in the essay, as well as Baldwin’s incredible sense of the “I” we were just talking about. You can imagine what it must have been like for Baldwin to be the first Black person these Swiss villagers had ever seen. He captures the kind of fear and fascination that his presence evokes, and he’s able to use that experience to write his novels. But he’s very aware of his place there. You know, pun intended, your place as a Black person. Place in the sense of “I’m in Europe, I’m a foreigner and a stranger.” Many of the villagers think Baldwin is African because, for them, Black people come from Africa. Their conception of an American is a white person, so Baldwin can’t be from America, he must be African. All of that stuff is in this essay. It’s interesting to me that other people have returned to this essay. Teju Cole wrote a beautiful long essay in the New Yorker about going to the same village where Baldwin lived. Teju is from Nigeria. He’s an African going to this Swiss village and tracing Baldwin’s footsteps, but Beyonce is on the stereo in the clubs he passes by. The world has changed. The essay is actually quite beautiful. I go back and read it occasionally. It’s a great homage, but also a critique of Baldwin. One of the things that Baldwin does in that essay is imagine Africa. He says, go back a couple of centuries and you find Europeans in their glory, listening to Bach and Beethoven, but go back a couple centuries for him and he’s in his African village waiting for the conquerors to arrive. Teju Cole takes Baldwin on and says, “No, you’re in your African village listening to this music, under the rule of this political system, with this kind of culture around you.” Africa is not a void that was waiting for the conquerors to come. Baldwin’s imagined Africa is what you see in that essay, not the reality of African history. So, my engagement with the essay is about seeing all those things. There’s another issue there too. The paintings I’m making with the full text of the essay are the biggest paintings I’ve ever made. The reason they are this big is because at a certain font size the entire text of the essay lays out to be 10 by 45 feet. The text itself determines the size of the painting. But it’s also a great excuse for me to try to see if I can do something like this, make a painting that’s 45 feet long. I’m engaging a different kind of tradition than when I make an 8-by-10-foot painting with a text that looks like a page. These paintings don’t look like pages: they look like panoramas, they look like landscapes, they look like Barnett Newmans. It was exciting to me to try to tackle that. I also feel like I’m at the end of this investigation. It’s taken me all these many years to get to the point to see if I can tackle all of Baldwin, use all of the essay. Before, just using fragments of it was hard enough. That was all I could manage. Now I’m ready to take on all of Baldwin. I think it’s the end for me. I’m interested in other things now, other ways of working. These paintings also respond to the pandemic in some ways. The studio I’m in now was only available because it was a co-working space and nobody wanted to co-work in the middle of the pandemic. Suddenly this big space in the studio building I was already in became available and I had a wall on which you could put a 45 foot painting. The opportunity of this space produced the opportunity to make the paintings.

Rail: Has the isolation of the shutdown given you more uninterrupted time in the studio? I know that’s happened for a lot of people.

Ligon: Everything that was on my schedule was postponed or cancelled. Suddenly, I had a year more to do what I needed to do. It has changed the way I work. Paintings could be turned to the wall for three months because they didn’t have to go out the door. Then I could turn them back around and say, “Oh, I need to work on this some more.” I’ve never had that kind of luxury before. Even though the Hauser & Wirth show was postponed for a year, I’m still working up until the deadline. Hopefully this giant painting will be dry by the time we need to ship it to the gallery. The leisure of letting things sit for a while without the pressure of deadlines or studio visits has been tremendous. It was really good for the work to slow down the process of making. I wish it hadn’t been at the expense of over 700,000 deaths in the United States alone, but that is the situation we find ourselves in.

Rail: Sadly, it is. Maybe viewers will have more time as well. You mentioned Barnett Newman. As with his work, these are paintings in which viewers will be able to immerse themselves. I wonder if one of the things that might get clarified with this show is your relationship to Abstract Expressionism. I remember once being at Irving Sandler’s apartment and seeing a Joan Mitchell from the ’50s and one of your works on the same wall. It gave me a new perspective on both of you. There’s another connection to be made in the fact that your show at Hauser & Wirth is following their Guston exhibition.

Ligon: I am flattered to follow Guston. I don’t paint the way he does at all, but his importance to me is his bravery to change, the transition from the Ab Ex work to the Klansmen, to throw away his good reputation as an abstract painter in order to tackle that subject matter. Before we were talking about how things get read differently over time. Those Klansmen paintings in the context of 2021 America get read very differently than they were read in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Guston’s saying, “that’s me.” If you make a painting called The Studio (1969) and it depicts a Klansman painting a painting, there’s not really any separation between “those people” and him. It’s a self-interrogation, or acknowledgement of white supremacy and its systemic nature. I think it’s super interesting in terms of discussions about those very subjects now.

Rail: Yes, especially for a white artist to be addressing this. In 2016 when controversy erupted around Kelley Walker’s show in St. Louis of his Black Star paintings, I went back and read your 2010 piece in Parkett about that work. You acknowledge that the paintings are problematic and difficult, but what you find valuable is that Walker is engaging with what it means to be looking at African American culture in the United States from the perspective of being a white artist.

Ligon: Well, we know how that story ends: [Laughs] Instagram posts by museums celebrating Black Lives Matter.

Rail: I saw on your Instagram feed over the summer that the CB2 store in SoHo put up a poster of one of your works in their window without asking your permission. Before that the Met and SF MoMA had posted works of yours, again without asking permission. In all three cases you made it very clear publicly that this was not acceptable.

Ligon: The CB2 thing is a complicated story, which you can’t totally unpack on Instagram. But in terms of the Met and SF MoMA, it was what the kids call virtue signaling: “Oh, we have these African American artists in our collection, let’s put their work up on our Instagram feed to signal that we’re down with the cause, down with the struggle.” What I noted in terms of the Met was that the artworks they referred to were a set of prints. That’s all they had in the collection. One would think that when a museum puts up an Instagram post and sends it out to their hundreds of thousands of followers, they have the work of that artist in their collection, they have a commitment to the artist, that there’s a significant holding there, that they’re aligned with the values that that artist espouses in their work. The Met owns four prints! [Laughs] But they’re putting up an image as if there’s a vast holding of my work and they’re so committed to it. If the Whitney did that, it would be a different story. They have probably every print work I’ve ever done. I just had to call it out. It was an easy gesture that didn’t mean very much.

Rail: I think it’s great that an established artist is raising these issues, not because of royalties or copyright, but from an ethical perspective. It says to younger artists, you have the right to control how your work or images of your work are used. You’re doing a public service.

Ligon: Here’s a stranger example. There’s a woman named Rachel Dolezal, who is basically a white woman who decided that she wanted to present herself as an African American and she got called out by her parents. She’s an artist, too, as well as a community organizer, and was the head of an NAACP chapter on the West Coast, a position that she got booted out of when it was discovered she’d been passing for Black. Someone sent me an image from her website that was basically this stenciled painting with the names of Black people who had been killed by the police. It looks like one of my early “Door” paintings. I just put up a post with an image of her work and the comment, “They say imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Does that include blackface? Just asking.” It’s not like I own black-and-white text paintings made with stencils. I took that from Jasper Johns. But what was interesting was her history as a person who was pretending to be something that she was not, and that now she is an artist making work that was “inspired” by sources that she had not named until she got called out on Instagram. It was funny to me, a joke. Some people said I should sue her, but why? Actually, she gave me a gift. One of the descriptions on the website said her work was “distress-textured.” I thought, that’s really good. I’m going to use that. So thank you, Rachel.

Rail: As a poet, I’m fascinated by your relationship to poetry. I love the neon piece where you use the Roberto Bolaño quote, “Only poetry isn’t shit.” In another neon work you use Muhammad Ali’s condensed poem “ME. WE.” You’ve talked about how poetry is important for you, but what strikes me about looking at the paintings is that you almost never use poetry as a source text. I have some ideas about why that might be, but I would like to hear why you have steered away from poetry as something that goes into the paintings.

Ligon: It’s an interesting subject. There is another neon piece that’s up now in a show in Athens that uses nine translations of the last two lines of Cavafy’s “Waiting for the Barbarians.” But you’re right. With one or two exceptions, I’ve never really used poetry as the basis of paintings. I’ve used poetry in neons because neon has a certain kind of clarity. It’s the one form that I reserve for poetry, whereas the paintings, which are all about opacity and the disappearance of language, don’t use poetry. I don’t know if I have a good answer for you. For the piece that uses Cavafy, I was really interested in how each translation is so different. Looking at the Greek original, nine different translators came up with their versions of it, including Google Translate, though an older website, Babel Fish, which I don’t think even exists anymore, did a better job at translating than Google. But I’m curious to hear your theory about my relationship to poetry.

Rail: Here it is: I think that what you do in your paintings is a kind of deconstruction of texts, what Derrida called the self-undoing of language. By repeating a text over and over and making it progressively more illegible as you descend down the painting, you bring out the contradictions, the hidden meanings, the various associations in these texts. It’s almost an act of violence towards your source. I think that with poetry this has already happened. In good poetry, great poetry, real poetry, the poet has already subjected their language to that kind of process. To do it in a painting would almost be redundant.

Ligon: Interesting. I think you’re spot on. Now that I’m thinking about it, one poem I’ve used in a painting is a little fragment of a Rita Dove poem called “Canary,” which is about Billie Holiday. The line I use, repeated over and over again down this long door panel, is “If you can’t be free, be a mystery.” Imagine that repeated to illegibility. In some way, that’s exactly what the poem is about. In my painting, that sentence from Dove literally becomes a mystery. Strangely enough, this is why poetry is important to me, and this is why I always have trouble with it. It has just now occurred to me, 25, 30 years later, that the title of the poem “Canary” refers, obviously, to canaries in a coal mine. That’s how we make music, creating songs under oppressive conditions, and also how we warn about what’s coming.

Rail: And coal dust is one of your chief materials! Another absence I noticed in your work is any language other than English. Was that a conscious choice? I am willing to bet that someone along the way has invited you to do something in another country in a different language.

Ligon: I have made works in other languages: a neon from 2018 titled Untitled (Siete Ospiti)—which says “you are guests” in Italian—and text drawings in both French and Italian, for example. The problem for me is when you don’t know a language well, and you’re trying to, as you said, deal with the deconstruction of language, you get into trouble. In any language, words mean different things, simultaneously. For example, I did a show in Paris, and I was using a Gertrude Stein text from Three Lives. In this Stein text, there’s a sentence that says one of the characters, Rose, doesn’t have the warm broad glow of negros, which Stein calls “negro sunshine.” I used those two words, “negro sunshine,” to make a series of drawings. Well, the French translation of the Stein is soleil negre so I used that for these drawings because I was showing in Paris. When the show was up, someone said, “you know, negre doesn’t mean Black, exactly, in French, it’s more like nigger.”

Rail: And negre has a second connotation in French of “ghostwriter.”

Ligon: Yes, exactly, which is also “nigger” because it’s unacknowledged, lowly paid labor. You were worked like a slave, you were worked like a negro. But that resonance wasn’t apparent to me. I just took the words from the French translation of Stein’s novel. Got myself in a little trouble there by not understanding the nuances of the language. I use English because I understand its uses much better.

Rail: To some extent you’re a painter and you’re a writer. You just happen to write with other people’s words.

Ligon: That is very generous of you.

Rail: You’re a writer like Borges’s Pierre Menard. In that story Borges makes the observation that when Cervantes writes Don Quixote in 17th-century Spain it means something very different from Pierre Menard writing exactly the same words in 19th-century France. Something similar happens with the texts you use: they take on different meanings because they’re in a different medium and they’re presented in a different period in history. And if we think of you as a writer, it makes sense that you work with English. We wouldn’t expect Baldwin to start writing in Spanish or French. But you use such a range of English. Your Richard Pryor paintings are very different from the James Baldwin paintings.

Ligon: Yes, for one thing, it’s speech versus the written word. The Stein is interesting, too. I think one of my projects was a kind of rewriting of Stein. If you read that part of Three Lives where she’s talking about Black characters, Rose and Melanctha, the descriptions are brutal. She has no love for Black people. When I started using “Negro Sunshine” I was aware that I was decontextualizing those two words from quite a harsh description of Black humanity. I was rewriting Stein just by using it.

Rail: I think you were doing her a favor.

Ligon: Stein is certainly a writer I admire, but one can’t get around her views of the Black characters.

Rail: Over the summer I was reading Henry James’s novel Roderick Hudson, which is about American artists in Rome. I love James, but I stumble over his casual anti-Semitism. What do you do with that? Do you just say, it’s a historical condition? Or do you refuse to read him? With Three Lives, you could have just said, “Stein is a racist, this is a racist text, this book is completely tainted and poisoned.” Instead, you engaged it. There’s a redemptive aspect to what you’re doing.

Ligon: I can’t accept the “historical condition” approach. When I hear the excuse that someone was just “a person of their time,” I think, well, Frederick Douglass was a person of his time, and Donald Trump is a person of his time, so that argument doesn’t go very far with me.

Rail: My wife, Heather Bause Rubinstein, and I were really happy to have a work of yours, Come Out Study #8 (2014), in Under Erasure the exhibition we curated at Pierogi in 2018. One of the things we were interested in doing with that show was questioning the distinction between the artist and the writer. What happens when a piece of erasure poetry is hung on the wall next to a Jenny Holzer “Redaction Painting” or a Charles Bernstein typewriter Veil poem is paired with scored-through work by Joseph Kosuth? As someone who has been so involved with putting words under erasure, I wonder if you are aware of the genre of erasure poetry, which has exploded since the 2016 election.

Ligon: I am not, actually. Give me some names! [Laughs]

Rail: Robin Coste Lewis, Mary Ruefle, Travis Macdonald, who did a really great erasure work with the 9/11 Commission Report. One of the pioneers is the British artist and writer Tom Phillips who has been working on the same obscure Victorian novel since the 1960s. Now that I think about it, Phillips’s obsession with this novel is similar to your lengthy relationship with Baldwin’s “A Stranger in the Village.”

Ligon: Robin Coste Lewis I know, but not Tom Phillips. I will look him up. Sounds right up my alley.

Rail: I wanted to ask you about public art. The one public art piece I’m aware of is A Small Band, the piece you did for the 2015 Venice Biennale with the words “blues, blood, bruise” in neon, which is certainly a poem. It’s currently on the façade of the New Museum. Have you done any other public art?

Ligon: Not really. I’ve done proposals but I find there are too many cooks, too many hoops that have to be jumped through to do a public project. And they take such a long time. I did a project with Whitman’s Leaves of Grass at the New School in their event space. Since you can see it from the street, I guess it’s semi-public. It took almost five years to get it done with all sorts of twists and turns. I don’t find the process that interesting anymore. I just want to get it done. Some people thrive on that. I don’t have the patience.

Rail: I guess you have to be like Christo and Jeanne-Claude where the process becomes part of the work. Or you can take the approach David Hammons did with Day’s End and say “Here’s a sketch of my idea, just figure out how to do it.”

Ligon: That’s genius. Six years later his napkin sketch has turned into a full-fledged public artwork. That’s how I would like to work, but I’m not as much of a pirate as David is. [Laughs]