ART WRITING

INTERVIEWS WITH ARTISTS

GUILLERMO KUITCA

Global Order, 1999. Oil on canvas, 74 x 74 inches. Collection of the artist. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

GUILLERMO KUITCA

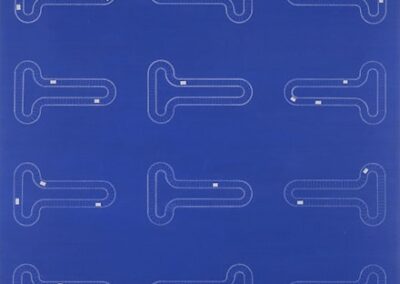

Untitled (Unclaimed Luggage), 2001. Oil and pencil on canvas, 76 x 77 inches. Daros Latinamerica Collection, Zurich. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York

GUILLERMO KUITCA

House Plan with Tear Drops, 1989. Acrylic on canvas. 79 x 63 inches. Walker Art Center, Minneapolis. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York.

GUILLERMO KUITCA

The Family Idiot, 2019. Oil on canvas in artist frame, triptych, 36 3/8 x 73 1/4 inches. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

GUILLERMO KUITCA

Untitled, 2014. Oil on wood; four-panel installation, 102 3/8 x 176 x 124 inches overall. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Sperone Westwater, New York.

GUILLERMO KUITCA

The Family Idiot (Sleeper in the Mirror), 2019. Oil on canvas in artist frame, 13 3/4 x 17 3/4 inches. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth. Photo: Gonzalo Maggi.

GUILLERMO KUITCA

David’s Living Room Revisited, 2014–2020. An installation by Guillermo Kuitca created from an installation by David Lynch, with the participation of Patti Smith. Collection Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

GUILLERMO KUITCA

Del 1 al 30000, 1980. Ink on Canvas, 39 1/4 x 78 3/4 inches. Private Collection, Buenos Aires. © Guillermo Kuitca. Courtesy the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

GUILLERMO KUITCA with Raphael Rubinstein

“Empathy has to be born from addressing what the artist is not seeing as well as their intentions.”

Although I was first introduced to Guillermo Kuitca in New York in the early 1990s by Lacanian Ink editor Josefina Ayerza, whose SoHo loft served as an unofficial salon where young artists from her native Argentina made contact with the New York art world, it was only in 2019 that I finally visited the artist at his Buenos Aires studio. The reason for my long-delayed visit was a monograph I was writing on his work for Lund Humphries’s Contemporary Painters Series. The conversation we initiated in Buenos Aires amid his recent “Family Idiot” paintings (shown in May–August, 2019 at Hauser & Wirth, Los Angeles) were picked up again during his visit to New York last fall when we sat down to talk at the Rail’s offices. As well as asking about his paintings, old and new, and the shifting reception of Latin American art in the US, I wanted to hear about Kuitca’s curatorial collaborations with the Cartier Foundation, the latest of which was a project for the Milano Triennale. (Originally scheduled to debut in April, the Triennale was postponed to an undecided future date when the COVID-19 pandemic began to devastate Italy.)

Raphael Rubinstein (Rail): I was listening to the news this morning and heard that the Peronist Alberto Fernández has just been elected President of Argentina. This comes at a time when Argentina is in the middle of yet another economic crisis. I was wondering, from your perspective in Buenos Aires, how the endless series of economic crises has affected or shaped the Argentine art world. Audiences in the US may know something about Argentine art, but maybe not so much about the actual conditions on the ground.

Kuitca: There is a cycle of economic crises in Argentina about every 10 years, though none have been as bad as the economic crisis of 2001. Then, artists not only had to live through the challenge in economic terms, but also made works that were profound responses to the crisis. I don’t want to sound nostalgic because nobody wants an economic collapse, but nothing since compares to 2001. The early 2000s was the first time that there was an awakening in the Buenos Aires art world to the economic crisis in particular. Most of the time art was reacting to politics or to historical tragedies but it seemed that those were disconnected from economic conditions. At some point we realized that they had to be resolved together.

Rail: Around 2000 you were making your “Global Order” paintings, which used the language of architectural plans to map the world. Were they in some way a response to Argentina’s economic collapse?

Kuitca: It was a time when it was hard to ignore geopolitical realities, and not only because of the Argentine crisis. There was also 9/11. But how art relates to the political isn’t always obvious. I often give the example of a work I did in 1989, a very large mattress with a map of Afghanistan. After 2001 that work was completely transformed by history. It became a very geopolitical statement.

Rail: That happens even more dramatically with the “Luggage Carousel” paintings, which you showed on the eve of 9/11 and which took on a totally different meaning once airports became scary, sinister places. You rarely make work that’s explicitly about a historical or political subject yet your work is often interpreted that way. It’s seen as being about Argentina’s Dirty War or about the Holocaust. I’m impressed by how you accept those readings, even while you make it clear that this wasn’t your intention. It’s an admission that the artist doesn’t really control the interpretation of their work, that what happens to the work once it goes out into the world is unpredictable.

Kuitca: Actually, I don’t know what my work is about. There is at least one painting, House with AIDS (1987), which is more specific, but in general there aren’t any specific references. As for controlling the life of the work outside the studio, I understand how partial and personal it would be to impose my own interpretations. So it’s not only that I don’t reject other people’s interpretations, but also that I don’t want to impose my own. Yet, I do have a vision of what I’ve done, and a sense of what it was about. It suddenly strikes me that you and I have been talking together for a long time and we’ve discussed my work in so many different ways, yet somehow we didn’t address what it was about!

Rail: It’s true. I’m aware of that. I feel that to ask you what the “House Plan” paintings, for example, are about is so reductive. For me, a lot of the power of your work comes from the fact that you’re not explicitly telling the viewer what the subject is. In some ways that’s an old-fashioned approach, a way of communicating through symbolism. You’ve said somewhere that the idea of open symbolism is something you got from looking at Pina Bausch. That makes so much sense. After all, what is a Pina Bausch dance about? What is Café Müller (1985) about? It’s about everything and nothing.

Kuitca: One of my first impressions with Café Müller was that it felt like it was my own work. It was a very strange kind of epiphany. It was as though I disappeared as an artist and she just appeared and her work was mine. Obviously I had nothing to do with the creation of Café Müller. [Laughs] It was the kind of experience that happens when you’re 19 or 20. I don’t know if we keep that flexibility and openness as we get older. What I got at that moment was that when you don’t know what you’re doing, in a way you know everything. If you’re a painter, everything you do is specific even if it’s in a vague or an accidental pictorial situation.

Rail: I think your ability to be in that position of not knowing is related to the fact that over and over you’ve changed your approach to painting.

Kuitca: Like the cycles of economic crises [Laughter]!

Rail: If you had continued to make “Map” paintings, or “House Plan” paintings, or the “Beds,” as I’m sure lots of people would have been happy to have you do, you would’ve been in increasingly familiar territory. Instead, you close one door and open another, and suddenly you’re making a completely different kind of painting. I don’t think you consciously make those decisions but I wonder what are the events or feelings that lead up to that “okay it’s time to change” moment. Is it an accidental discovery? Do you do something in the studio and think “Oh that could be a new body of work”?

Kuitca: It’s pretty much what you said about the doors. It’s also about lack of curiosity in the old work and how curiosity leads you to something else. Though my work is quite different from a couple of years to the next, it moves in a kind of circle. Some subjects never really go away, but I don’t do that consciously. I don’t sit in the studio and say, “Today it’s time to change my work.” I feel that I am the same artist. I am doing different works but I’m not a different artist. I think the curiosity of going in a different direction means that after a certain amount of time I stop being engaged in what I was doing. I try to go as deep as I can but I can’t if there’s nothing new there. Normally I work through the years and when it’s time to do a show, I edit what I’ve done and somehow that ends up being a body of work, but it was different with the “Family Idiot” paintings. For this particular suite I didn’t know what I was going to do but I put myself to work, and somehow once I completed that cycle, I felt that I didn’t have much to add.

Rail: I wonder if when you were working on the “Family Idiot” paintings you were thinking about how they would look in Hauser and Wirth’s Los Angeles gallery?

Kuitca: I knew that the space was quite monumental, that the walls were very big, so I decided not to try to compete with the space and go with smaller sizes, and activate the scale. That happens in my paintings all the time, small things in large vast spaces. That was probably the only decision that was made, to reduce the size of the work.

Rail: The “Family Idiot” paintings obviously reconnect with what you were doing in the early 1980s, like those vast theater stages in the “El Mar Dulce” series. In both “The Family Idiot” and “El Mar Dulce” you rely on illusionistic space, which is so different from the diagrammatic space of the “Maps” and “House Plans.” It’s rare to see you look backwards. You’re always starting anew.

Kuitca: I didn’t plan to go back. It’s in going forward that I’ve found connections to the past. These are new paintings, completely affected by the experience of the “Cubistoid” works I began in 2007 as well as the diagrammatic paintings of the 1990s and 2000s. The spaces constructed in these new paintings happened in a more organic way than the paintings from the 1980s where I was working with figures and dramatic situations. These spaces are a lot more angular and less prop-y, less simple.

Rail: And more dreamlike.

Kuitca: That’s right.

Rail: The ’80s theater paintings are plausibly depictions of real stages. They have a sense of an actual space. But the “Family Idiot” paintings depict an impossible architecture, with walls that could be transparent, or could be mirrors. They employ the power of painting to create impossible spaces.

Kuitca: Well, the mirrors fucked up everything. I found that once I started to play with them the situation got so complicated. I felt like I was juggling. Every time the mirrors appeared I said to myself, “Oh no, not again!” I regretted introducing them but of course paintings follow a logic of their own.

Rail: The relationship between painting and mirrors has such a deep history. This subject has been on my mind because I just finished writing an essay about Albert Oehlen’s 1980s “Mirror Paintings.” Those are paintings where Oehlen glues real mirrors onto the canvas to disruptive effect. The space in a mirror is at once real and virtual. I have a theory about your work relating to real and fictive space that I’d like to try out on you. We know that space is a constant in your work: lived-in spaces, cartographic spaces, the dreamlike spaces of the “Family Idiot” paintings. There’s only one body of work that doesn’t address space, the “Desenlace” paintings done in what you’ve called a “Cubistoid” style, which are essentially abstractions with only a very residual sense of space. I noticed that it’s only when you stop painting “spaces” that you begin to make murals and installations. I’m thinking of the mural in your studio in Buenos Aires, the wall paintings for Hauser & Wirth’s Durslade Farmhouse in England, and the three-dimensional structures you’ve shown in Sperone Westwater and other galleries.

Kuitca: Yes, exactly! It was an irresistible consequence of the Cubistoid paintings, which were a kind of liberation. I was never considered an abstract artist because diagrams were such a rich zone that I could postpone the question of representation or abstraction. The diagram does not fall into either category. I liked not having to deal with the figure or with abstraction. But the Cubistoid paintings were an eruption of a different language. I didn’t know where they came from. I just accepted the possibility of painting abstractly by inhabiting a visual language that is so specific. I didn’t turn to Cubism as historical pastiche or as a postmodern gesture. It appeared as something that I found myself. It was very fluid, and I enjoyed myself very much doing these paintings that were intended to represent Argentina for the 2007 Venice Biennale. But as you said, the consequence of that was immediately moving from the canvas to the wall. These paintings were viral. They started in one space and they moved to another.

Rail: Maybe because there’s no necessary limitation to the Cubistoid paintings. A map is of a specific area, either small or large, and a house plan or a theater seating chart is that space and nothing else. It has limits and boundaries. In the Cubistoid paintings there’s no inherent, intrinsic stopping point. I love that you describe them as viral.

Kuitca: Because I basically couldn’t stop. Painting murals, you get very conscious of accidents in a room, like when the wall turns or folds. Angles were fine but folds weren’t. Whenever I get to an architectural detail that would make the painting look like wallpaper, or something that is wrapped, I’ll stop. I once tried to sort of camouflage some of the electrical sockets or switches for fans and it didn’t work. In this paradoxical way, camouflage makes things more visible than when you ignore them. All those little gestures in rooms were the echo of the limitations I had with the architectural plans.

Rail: So no trompe l’oeil effects. You want us to be aware that we’re in a room surrounded by solid walls with paint on them.

Kuitca: Yes. I also like that the work only exists in one place and can’t travel. I’d like to continue to do murals, maybe on a different scale, and more public.

Rail: Murals also resist the camera, resist photography. It’s easy to have the illusion when you look at the photograph of a painting, even on your phone, that you’re somehow seeing the painting. But in the photograph of a mural, you always know you’re only getting a very partial, limited sense of the experience. Staying with the Cubistoid paintings, you once mused that they could have been painted by some obscure early 20th century Latin American Cubist. I think you imagined an artist like Alfredo Hlito, even though he wasn’t a Cubist. There’s a great Hlito from the Cisneros Collection in the new MoMA. I remember you saying to me in Buenos Aires that you didn’t have a chance to see much Argentinian modernist painting when you were growing up.

Kuitca: Yes, those works didn’t become visible until maybe 25 years ago. The only Latin American modernist art I might have seen was some Brazilian Neo-Concrete work. When I was 16 or 17 my mother took me on a vacation to Rio de Janeiro, which was a popular destination for Argentinians at the time because of the currency exchange rate. We happened to go to the Museum of Modern Art there. This was before the big fire that destroyed most of the collection. I have the very strong impression of seeing some Neo-Concrete art. But I didn’t see anything Argentinian. When I met Hlito in the late ’70s he was doing a very different kind of painting. I was very, very young, but I was able to visit him in the studio. I hadn’t seen the concrete works he’d done in the ’40s. It’s only more recently that avant-gardes in Argentina started to be recognized. When I was a young artist there was not much of a ground, not really a past. We weren’t working on the shoulders of anyone. It was kind of a wasteland. Of course, there were some masters that I had happened to see in galleries, but those were more expressionistic paintings from the ’60s.

Rail: Like Jorge de la Vega?

Kuitca: Yes, like de la Vega, who was so good! By that time de la Vega was probably dead. But as for the Argentinian concrete work, it was something that only became part of my history when my history was already written.

Rail: This raises another question about your identity as an artist from Latin America. When you first started showing outside of Argentina, first started showing the United States, in the second half of the ’80s…

Kuitca: No, it was actually later, almost 1989.

Rail: I don’t mean solo shows but group shows. In 1987 you were included in The Art of the Fantastic.

Kuitca: Yeah, that’s right.

Rail: At the time you and other artists like Julio Galán, who was also in The Art of the Fantastic, were categorized under the theme of magical realism. This supposedly was the only way a US audience could view a Latin American artist. I think that’s something you resisted.

Kuitca: Yes, strongly.

Rail: Could you talk about that?

Kuitca: I had nothing to do with magical realism. At the time Latin American art did not exist beyond the Mexican muralists and Frida, who was a rising star. I was warned when I started showing outside of Argentina, first in Brazil, and then in Europe, that in order to make an appearance in New York I should avoid any galleries that specialized in Latin American art. I was also advised that if I was going to make a show in Europe it should be in a gallery that didn’t show Latin American art, but was more international. If you were from Latin America there was the idea that you could only do two types of work: so-called magical realism or political art. There was pressure that if you were an artist from a specific place your work should either address specific issues or look a specific way. My work did not fit into either magical realism or political art, even though I was in The Art of the Fantastic, which drew on a certain tradition of Latin American art, like Wifredo Lam, Botero, Tarsila do Amaral. At some point Julio and I were starting to have shows in similar galleries and we both ended up showing with Annina Nosei in New York. Maybe he had his first show in ’89 and I had my first show in ’90, but I had met Annina before and I said, finally, “Okay, maybe this is a place where I could see my work in a different context.”

Rail: Had you been spending time in New York before then?

Kuitca: No. I first came to New York when I was seven or eight years old. Then I came by myself after a long trip in Europe when I was 19 and I was kind of lost. That was the trip that took me to Wuppertal and I had been in London.

Rail: Is that the same trip when you saw The New Spirit in Painting at the Royal Academy?

Kuitca: Yes, but I didn’t return to New York until almost 10 years later, which was strange because I was traveling a lot in the ’80s in Europe and Latin America. In Latin America I traveled mostly to Brazil. In Europe I traveled mostly to Holland and Spain because those were the places I was able to show more of my work. Obviously, I am a Latin American artist. I never had a problem with being Latin American. I had a problem with being categorized. So in the ’80s I was not in New York at all. It took a long time to come back here.

Rail: But New York is important to you in other ways. For instance, you used to go to the Rand McNally map store to stock up on maps.

Kuitca: Once I started to come back I visited three times a year.

Rail: Did you ever think about living here?

Kuitca: No, I never thought about living anywhere other than Buenos Aires.

Rail: Was discovering the Rand McNally map store like being a child in a toyshop?

Kuitca: Yes, exactly! I bought so many maps but not compulsively because I was very specific about what I was buying. I like to put myself in the eye of the salesperson at the counter saying “Where is this man going?” because there were maps from everywhere and at every different scale. I was looking at maps because of their density or the opposite of the density. I was looking at maps in a way that had nothing to do with destination. In New York I started to grow my library of maps. Obviously things were very different in the pre-internet era.

Rail: I don’t know if the Rand McNally map store still exists. Probably not. We were talking before about how the meaning of some of your paintings has changed because of historical events. In one way the meaning of all the “Map” paintings has changed. Printed maps were still in common use when you made them, but now they’ve almost disappeared. In addition to all the geopolitical events that have changed the way we might look at a map, the map itself is now something that we mostly experience digitally.

Kuitca: Plus, with our digital devices we have become so aware of where we are at all times. I’m very happy I did the “Map” paintings then, otherwise I might have lost the subject completely. I don’t think I would be able to do those paintings now.

Rail: There’s a closer relationship in the translation of a printed map to a painting than how painting might respond to this virtual, digital, invisible network. How do you depict or respond to something like that in painting? It’s not impossible, but it is different.

Kuitca: It’s important, I think, that I made maps where you could get lost. Not because they were tricky or were wrong but simply because I don’t think those maps were about location. In a way, pictorial language dislocates pretty much everything, even if you copy something perfectly. If you translate it in identical terms it’s still a big painting. It’s somehow a crazy referential space. So in a way I always thought that those paintings were a place to get lost in.

Rail: Yet your paintings are still maps. They contain and convey information. They are real and concrete. To me, that’s a fundamental part of a lot of your work. Andreas Huyssen talks about how your art is a way of knowing the world. Even though stylistically your work is very different from Jean-Michel Basquiat’s I think both of you draw concrete information into the work. You said, a long time ago, that your paintings are about trying to understand the world in which you live.

Kuitca: I’m happy that you put an accent on these things. Because I’m an artist it was often assumed that those maps were invented, that they are fantasies. But they are not. They contain real information. People forget that my maps are of real places not invented ones.

Rail: They’re not Borgesian.

Kuitca: No, they’re not. In one painting I switched one name for a repeated name but that’s the only time a “fantastic” place appeared. The interesting thing is that this fantastic place appears in a very realistic context. It’s a transpolitical name in an accurate geographical space. But most of the maps were not invented. When I painted genealogical charts or maps with the names of people instead of places, those names were concrete. I took them out of a telephone book. Very often people ask me, “How did you come to put this name in this painting?” How should I know? [Laughs]

Rail: It’s an example of people wanting to pin things down and say, “Oh, this is what the work is about.”

Kuitca: I think it was sometimes unnerving for people that I almost never painted any places in Argentina, that there was no autobiographical reference in the work.

Rail: There is an almost impersonal quality to your work. It’s recognizably yours in terms of style, but you explore the world as it’s mediated through institutions and systems of representation. This is why your work resonates so much with Foucault. But let’s come back to your recent “Family Idiot” paintings. It’s an unusual title, which I know you took from Sartre’s book on Flaubert, L’Idiot de la Famille [The Family Idiot].

Kuitca: When I started I didn’t have a title. Oddly enough, the book I was reading then was Le Mots (Words), Sartre’s beautiful autobiography. Then I came across the title L’Idiot de la Famille and it was magnetic. It was such a good title for these paintings, but it was more than a title. It gave me a structure. Of course, I’ve never read L’Idiot de la Famille. It’s beyond my abilities to focus on such a long work, but I knew about it, and I started to read about it, which I realize is a superficial way to address a book, but the paintings aren’t meant to be about Sartre’s book. Ultimately Sartre’s study seems to be a kind of machine that applies all sorts of knowledge that he had at the time, from Marxism to psychoanalysis to philosophy to sociology to politics, a compendium of knowledge which he applied to Flaubert, a writer he was fascinated by but also despised. So many ambivalences. I thought it was such a fascinating project. I wanted to put these paintings in a domestic context, which obviously involves the family. This work isn’t self-referential, but I believe that family situations are crucial to most artists, regardless of our success or our failures.

Rail: So the paintings are in some way about being an artist, about becoming an artist?

Kuitca: Yes.

Rail: The fact that you haven’t read Sartre’s book reminds me of Martin Kippenberger—though I’m sure that you’re more of a reader than he was. Kippenberger would have other people read books for him and then tell him what they were about. For instance, he never read Kafka’s Amerika, which inspired his most famous artwork. He just had someone explain it to him.

Kuitca: Actually, I haven’t dealt with too many people who have read Sartre’s book.

Rail: Well, I certainly haven’t. It’s famously unreadable. Since finishing the Family Idiot paintings you’ve been working on a curatorial project for the Milano Triennale. Can you talk about that?

Kuitca: It goes back to 2014 when I was invited to curate a show at the Cartier Foundation in Paris. I had been impressed with David Lynch’s 2007 installation at the Cartier Foundation where he created a living room. I revisited his installation. He also intervened with my re-creation by adding paint over my painting. Also I asked Patti Smith to record a text. It became a very immersive installation. I also included works by Vija Celmins and Artavazd Pelechian, who is an incredible Armenian-Russian filmmaker. I consider him to be a missing link in cinema history. I also brought in works not in the Cartier collection. For instance, I knew how important Francis Bacon was for David Lynch—

Rail: And for you!

Kuitca: Yes, for me, too. So we had a small, beautiful Bacon portrait and also a painting by Tarsila do Amaral. The show was called Les Habitants, which is the title of a film by Pelechian. In 2017 I did a larger version in Buenos Aires titled Les Visitants, a word that doesn’t really exist in French but is very evident and understandable in Spanish. There it was mostly in monographic rooms. In one room I interacted with some photographs by William Eggleston. In April, the third installment will be at the Triennale building in Milan. I’m structuring the show in a different way. It won’t have monographic rooms. Instead there will be more interactions between different periods and geographical backgrounds. Curating is something I truly enjoy doing.

Rail: Maybe because of the theatrical aspect. In the early 1980s, when you returned to Buenos Aires after your time in Wuppertal with the Pina Bausch Tanztheater, you threw yourself into creating theatrical productions. Since then you’ve designed sets for operas and plays. And of course you have made many paintings based on diagrams of theaters. In some ways, curating, creating an environment for people to come into, has more to do with theater than with painting. You’re telling a story with works of art instead of with actors and props.

Kuitca: But I still have to figure out which story it is that I am telling. [Laughter] For me, curating has to come from feeling very connected to the artists. In this project I don’t change the works, as I did with David Lynch. He had a very funny approach. I asked him to make a painting, and the painting that he made was completely different from what I had in mind. He said in a very sweet way, “you ruined my work, now I get to ruin yours.” [Laughter]

Rail: Recently I asked Sonia Becce who is something of an expert on your work whether there were any contemporary Argentine writers I should read to better understand your work. She mentioned Ricardo Piglia’s book Artificial Respiration (1980), which tells the story about a man who is pursuing this mysterious uncle who’s left Buenos Aires for a small town on the Uruguayan border. The uncle himself is obsessed with researching the life of an obscure political figure from the 19th century. Piglia’s book is full of absences and missing people. It is seen as a kind of allegory of what happened in Argentina in the 1970s. Does it make sense to you that Sonia mentioned this book?

Kuitca: Yes, it does, but I thought you were going to say César Aira. When Aira visited my studio once he happened to see some of the cubist paintings I was working on. Afterwards he sent me this little book titled Triano (2015). I don’t think it’s been translated into English.

Rail: Was Triano inspired by your “Desenlace” paintings?

Kuitca: Not inspired by them, the book and the paintings just happened to converge. That’s why he wanted me to read it. It’s the story about him going with a friend of his, a great poet named Arturo Carrera, to take classes at a Cubist painter’s workshop in the little town where they are from. I found the book very lovely. As for what Sonia said about Piglia: I read Respiración Artificial when it came out and it made a very, very strong impression on me, but I never thought about it in relation to my work. As you say, it takes an allegorical or metaphorical approach. I’m not so sure how I would be related to that. I know I had a very hard time trying to take account of what was going on in Argentina until I made the “Nadie Olvida Nada” paintings. Other works that I did in an almost adolescent way to address the period of dictatorship I consider crap. I never show them. I also made From 1 to 30,000, which counted the missing people. All those years were very tense and very strong, each year for a different reason. There were days I would go to my studio—this was the first time I had a studio—and was only capable of writing out numbers. The “Nadie Olvida Nada” paintings were a sort of elliptical way to address what had just happened. Because of the Malvinas War and the dictatorship, 1982 was an extremely dramatic year, the most crazy year of all. I was in a more introspective mood. Maybe I found an echo of that feeling in Respiración Artificial.

Rail: I think that From 1 to 30,000, where you wrote out every number between 1 and 30,000, is a work that you had to make in order to free yourself to respond not just obliquely but also maybe more emotionally to events in Argentina. I also see From 1 to 30,000 as a farewell to the anti-painting of the 1970s. All the things that have characterized your work ever since, especially how you privilege space, are absent from that painting, it’s a very conceptual work. I feel like it allowed you to draw this line and start from zero as a painter and as a citizen of a country that had gone through a traumatic period. After that you could start to do the work of mourning and memory in works like “Nadie Olvida Nada.” After the “Nadie Olvida Nada” series, which was done with house paint on scraps of wood from around your studio, your paintings became much more sumptuous. I see them as connected to the “return” to painting that was happening in so many other places. After the austerity and reductivism of the 1970s, history and autobiography and art history and emotion and the seductive power of oil paint come flooding back in.

Kuitca: I see that, and obviously I can see my work in that context, but I also felt that my work did not come from the joy of painting. Maybe later the paintings became a little more grand and started to bring in theatricality, but the works that were formed out of that moment were so reductive that in a way it carried with it the reductiveness of the previous decade. I wanted to make something that was still a fully pictorial object, but in a way that was not necessarily a celebration of painting in the manner of Neo-Expressionism or Transavanguardia.

Rail: The idea of “Oh, now we’re painting again!”

Kuitca: I think I did not have that aspect.

Rail: Not everyone gets that. I think the biggest misinterpretation of your work has to do with the “Beds.” I was guilty of this too in the beginning. A lot of people look at them and when they see these small beds and they think, “children’s beds” and that sets off a whole train of readings. It was something of a shock when I read an interview where you explain that they’re small not because they were made for children but because you want them to be perceived as if they were far away. When you were making them it probably didn’t occur to you that they would be seen and interpreted as children’s beds.

Kuitca: When you do the work you have no idea what’s going to resonate. I thought the idea that these were shrunken beds made a lot of sense because of the “Maps” and “House Plans” serieses. But I guess children do seem to turn up in my work. All those small figures, for instance.

Rail: Or your painting titled L’enfance du Christ (1990) or the “Nadie Olvida Nada” paintings, which evoke childhood. On the subject of interpretations, and misinterpretations, have you noticed differences in the reception of your work in the US versus in Europe or Latin America?.

Kuitca: In the US there seems to be an urgency to create a very specific context and specific meaning around the artist, to say what the work is about. There’s not much time to let work breathe and develop.

Rail: I believe this is connected to the expectation that artists be able to offer a total interpretation of their work to the viewer. And this, in turn, comes from the way artists are trained in MFA programs. You’re expected to explain what you are doing in a quasi-academic language—

Kuitca: And in a short time—

Rail: Say why you made the work, what your references are, what it’s about. I find that not-so-interesting because where does it leave the viewer? In this predictable cycle between work and interpretation there’s no room for surprise. Maybe that’s what you’re encountering.

Kuitca: Yes, totally. I also found this attitude as a teacher and a visiting artist in the US. Ultimately that’s why I created a two-year program for young artists in Buenos Aires. Most artists I know don’t address things like they are preparing something in school.

Rail: But institutions—I’m thinking about museums here—want to be able to justify why they are supporting you, why they’re presenting your work. They feel they have to make it accessible to an imagined audience.

Kuitca: Art education and art institutions are so problematic. Of course, there are great artists who teach. What bothers me is the pressure you feel when you visit a student’s studio and there’s this preset discussion of the work. Sometimes it feels so disconnected from what the work is really about—if the work is about anything at all. For me, as a teacher, it’s very important that I always try to find time and space. One visit won’t forge a bond, or create a pedagogical experience.

Rail: What about you? I know you studied privately with one artist for eight years, and you didn’t go to art school. So you had a non-academic, non-institutional formation.

Kuitca: That’s actually something very idiosyncratic about Buenos Aires, which has a very rich story that I hope someone addresses one day. I was sort of talented as a young child, and even my parents were alert enough to keep me away from the art school. It was somewhat common knowledge that art school, at least in the ’70s, was not the place where artistic creativity would grow. Of course, the risky part was not being among your peers. Ultimately, however, you find your place. In Buenos Aires we created a network of workshops where artists work with other artists. So it’s not unusual for artists not to be academically trained, like me. In the US I can recall really great encounters with artists for short periods of time—for example, when I was at Skowhegan, which is such a great school. But the general idea of visiting an artist once and talking about what you see is problematic. Empathy has to be born from addressing what the artist is not seeing as well as their intentions. Dialogue comes from you sharing the same incapacity rather than simply offering a different illumination.