ART WRITING

REVIEWS

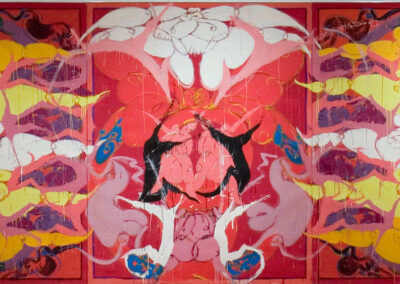

Norman Bluhm at the Station Museum

Houston.

Norman Bluhm (1921- 1999) is perhaps best known for his gestural abstractions of the 1950s and ’60s, canvases that range from dense fields of glowing color to dramatic compositions of jagged shapes and skittering lines sparring across finely splattered grounds. This show focused on a less familiar but, arguably, more important body of work, the large -scale paintings Bluhm made during the last decade of his life. By 1990, the date of the earliest painting in the show, Pythagorean Icon, Bluhm had developed into a very different sort of painter, one whose work was grounded in bilateral symmetry, art-historical references, extravagant decorative devices and quasi-abstract, highly eroticized figural forms. The sources of his thronging lexicon of compositional devices in his 1990s work range from the Netherlandish tapestries at the Cloisters in Manhattan and the designs of medieval goldsmiths to Botticelli’s angels, Baroque-era nudes by Rubens, Matisse’s The Dance and much more, including elements of Abstract-Expressionist automatism. Out of these he fashioned an array of swelling forms and calligraphic squiggles that he orchestrated into compartmentalized, hierarchical structures which take their cue from Sienese altarpieces. Employing multiple panels and an audacious palette that favors violet, pink and yellow, Bluhm’s late paintings are both fiendishly precise and copiously orgiastic. They also share a strong kinship with mandalas and other types of sacred art. The 10-by-25-foot Persephone (1995) depicts three giant arching niches bursting with pendulous violet growths. Ovoid and rectangular insets teem with stacked or abutting shapes that suggest naked dancers with attenuated and segmented bodies. A wild-looking but fiercely controlled visual rhythm of arabesques sweeps back and forth across the canvas. Capella lgnota (1997), as the title-unknown chapel, in Italian-suggests, ls strongly architectural, with columns, arches and pediments. Here, some of the figures take on an almost serpentlike character that is at once phallic and spermatozoid. The more one looks at these forms, the more their sexes meld, as when ostensibly female shapes evoke both breasts and testicles. In contrast to grand horizontals like Persephone and Capella lgnota, the 13- by-8-foot Ode to Apollo is a three-panel vertical work. Rising up through its center are gymnastically nestled forms of white, gray, purple and yellow. As always in Bluhm’s late paintings, the tips of these tapering bodies explode in ecstatic drips and splatters. It was Bluhm’s ambition to carry the energy and innovations of Abstract Expressionism into uncharted territory. As this exhibition proved, in the work of his final decade he accomplished this again and again by dipping Into the riches of art history and by assembling a powerful new language of painterly devotion, at once boldly erotic and deeply spiritual.