ART WRITING

INTERVIEWS WITH ARTISTS

Shirley Jaffe with Raphael Rubinstein

The Brooklyn Rail, April, 2010

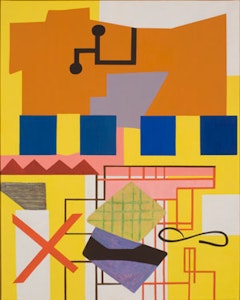

Can the same painting give us difficulty and joie de vivre? If you have ever encountered a painting by Shirley Jaffe, you know the answer to this question. If you haven’t, then you may be skeptical that such a thing is possible. You will have also, alas, missed some recent opportunities to see paintings by Jaffe in New York.

Tibor de Nagy presented a group of new paintings at the Park Avenue Armory Art Show in March, and also a gathering of paintings from 1969 to 2009 at the gallery’s Fifth Avenue space. It was during that show that I met with Jaffe at the gallery for the following interview. I’ve known Shirley since I was a teenager, and written frequently about her work, but this was the first time we had ever sat down to do an interview. I was a bit concerned about the (for us) unaccustomed formality of an interview, and also about Shirley’s well-known propensity to disagree with anything that anyone says about her work. She did, as expected, reject some of my observations but, thankfully, not all of them. I started off by asking her about some Parisian art world history (Shirley has lived in Paris since 1949), but what I really wanted was to ask her about her paintings, how she arrives at her unique brand of complexity, how her work has been evolving for the past 60-odd years, and how it continues to evolve.

Raphael Rubinstein (Rail): For the last decade your Paris gallery has been Nathalie Obadia, but for many years you showed at Jean Fournier. There were two groups of artists that Fournier showed: Americans like you, Joan Mitchell and Sam Francis who had been in Paris in the 1950s, and French artists such as Claude Viallat, Simon Hantaï and, in a younger generation, Bernard Piffaretti. I wonder about your relationship to these two groups. In the beginning, I suppose, you had a much more personal relationship with the Americans.

Shirley Jaffe: It was mostly Sam and Jean-Paul Riopelle who were instrumental in making Fournier interested in my work. At that time, I was closer to a kind of Abstract Expressionism. The other American was James Bishop, who was a little bit aside. Hantaï was the most important artist in the gallery at the very beginning.

Rail: Did Fournier show Martin Barré?

Jaffe: No, Barré was part of another group and, to my knowledge, Fournier had absolutely no interest in his work. Martin Barré was like a secretive French artist who belonged to another clan. It’s only now that we can see that there’s a kind of relationship to some of the artists that Fournier showed. At the time he was absolutely outside of it.

Rail: So, you felt, in the beginning, artistically closer to those Abstract Expressionist American painters.

Jaffe: Absolutely.

Rail: But did that change over time?

Jaffe: It changed when I went to Berlin. I had a feeling that my paintings were being read as landscapes, which was not my intention. I felt I had to clear out the woods. It started in Berlin and it continued when I came back to Paris. Fournier, and even my friends, were a little shocked. I felt that I had stepped out of the closed circle. And, I continued. But, Fournier, to his credit, as a dealer and as a person, continued to show my work, even without enormous enthusiasm. Then, I began to know all of these other French artists that he was showing.

Rail: As you moved from gesture to geometry, touch became less prominent, and that’s true of the French painters as well. In their different ways, Hantaï and Viallat were also trying to make paintings without that touch of the hand.

Jaffe: For me, it was quite different because I built up the painting by the gesture in the first period. But then I asked myself: What essentially did I want to say? What was I painting? I thought I had to start like a child, try to reduce everything, gesture and also significance. In the very first paintings it wasn’t geometry, more like “lite” geometry. The lines weren’t always straight. I kept elements of a kind of gesture in a certain section of the painting. And then, I began to develop on that. I had no clear program, mind you.

Rail: You’ve said that one of the things you got inspiration from in Berlin was contemporary music, composers like Xenakis and Stockhausen.

Jaffe: I listened to them, yes.

Rail: Can you remember what attracted you to their music?

Jaffe: It was the adventure that they were going through. It introduced me to new sound.

Rail: There was this break in your work in Berlin, but there are not that many breaks in your career, where one can point to a before and after. A lot of artists work in phases or periods. You can look at paintings made for a particular show and see that they form a recognizable body of work. With your paintings, apart from the break in the 1960s, and maybe another circa 1980, it’s very hard to sort them into separate bodies of work. I’m reminded of Morandi, an artist who is always evolving but very slowly and gradually. In your work, there’s no demarcation. Is this something you’re aware of?

Jaffe: The adventure of Morandi does not particularly interest me. It’s infinitely repetitious, and I don’t think I’m involved with that in the least. There have been different attitudes that informed certain groups of paintings, that helped me move, but they’re not detectable. They’re underneath the structure, maybe. I think they’re visible, a little bit, to a very trained eye. I’m much more interested in what kind of structure I can involve the spectator in that’s different and that forces them to perceive the world as it is.

Rail: I think there are some constants in your work, but one of the impressive things is that the work has changed so much despite these constants. Each painting is different from the rest.

Jaffe: I want variety. I mean, I’m not interested in that “one thing” and deepening it. I find that boring. I would be bored.

Rail: There seem to be lots of stripes in your recent paintings. Maybe a body of work is in formation.

Jaffe: That’s because I’ve been painting for a long time and perhaps my invention is thinning out. It’s possible. There are some paintings that have had more adventurous forms than those that I do now, but now I’m in New York and I’m beginning to have new ideas. What inspires me are things that I see in the streets, like looking up and seeing these immense skyscrapers. These visions force me to think: What else can I do next?

Rail: There are several recent paintings titled “New York Collage.”

Jaffe: Yes. That came because of the last trip I made here. I began to think that New York was filled with collage, that it wasn’t a flat, beautiful, even surface that I often see in Paris. Everything here is a collage. It’s all mixed up.

Rail: Your work actually has a beautiful, even surface. At the same time, it’s about disjunction. You could see the surface, control, and refinement of the paintings as more responsive to the landscape of Paris, and the overall clashing of shapes and colors and forms as something that belongs to New York.

Jaffe: Well, I’m fighting constantly, in Paris, against the evenness. I work there, I’m fed by what I see. But, at the same time, I’m fed more intensely by that collage of New York.

Rail: Have you ever been tempted to make collages?

Jaffe: No, absolutely not.

Rail: What makes it uninteresting to you?

Jaffe: The physicality of it. I don’t want to paste and cut. And I like to paint. I like the feeling of the brush. I like the stroke.

Rail: And you like to be able to change the shape constantly.

Jaffe: Yes. You could do that with paper, but I wouldn’t want to do it.

Rail: Do you still use pieces of cellophane with painted shapes to try out changes in your paintings?

Jaffe: Yes, I still do. An artist suggested cellophane to me as a way of saving the time of scraping down, and since then I’ve used it. But ultimately, I have to do it on the canvas even though it means trying out many potential solutions. When I hit on something I think is interesting, I try it on the canvas anyhow, without the cellophane, and then scrape.

Rail: I was wondering about the relationship between the gouaches and the paintings. You’ve said that for a long time you thought that your gouaches were more successful than your paintings, but that more recently you feel that the paintings are doing what you wanted the gouaches to do.

Jaffe: I enjoy doing the gouaches now and then. I like the visible change that I see. But, I want a kind of potency that I only think I can get in the paintings.

Rail: Does a specific gouache ever serve as the take off point of a beginning of a painting?

Jaffe: It might. But, it disappears. I never sustain it.

Rail: What about the more loosely painted areas that have been appearing lately in the paintings? Are these the gouaches migrating into the paintings?

Jaffe: It first happened as an accident, a way of introducing another surface without meticulously painting another kind of surface. It’s practically mechanical, but it was interesting to me because it broke up that sameness that was developing in my paintings. And I liked the fact that I could introduce something else as a material surface.

Rail: Could you talk about the annotated drawings that you make on index cards? How do they function?

Jaffe: They’re not drawings. Someone looked at them and thought they were drawings, but actually they’re notes. When I change a form I want to keep a record of it in case I want to come back to repaint that surface. I have to know what colors I mixed.

Rail: So, it happens while you’re making the painting. That explains the crossed out notations, which record the changing look of the painting.

Jaffe: For the most part, it’s a record of the color change; it’s not really for the form.

Rail: One of the earliest paintings in this show is “The Gray Center” from 1969. Years ago, you pointed out to me a painting by Magritte called “On the Threshold of Liberty.” It’s the one where a cannon is aimed at several stacks of framed images. I remember you saying that there were pictorial possibilities in that Magritte that hadn’t been explored yet. It surprised me that you were looking at a painter who was so different from you. I think “The Gray Center” shares something with that Magritte.

Jaffe: I doubt that I did it intentionally, but it’s true that one looks at a lot of paintings that have nothing to do with one’s particular direction, paintings that can give you some creative insight. The world is pretty large and other people’s visions are equally important, provided you feel that they have substance.

Rail: As long as we’re talking about Magritte, there’s a flatness, an anonymity in his paint handling that could relate to yours.

Jaffe: Léger much more.

Rail: I can see Léger being important for you, but what about Mondrian? In the small painting “The Door” from 2002 there’s a ladder shape that recalls Mondrian’s late New York paintings.

Jaffe: Certainly my eyes have been informed by Mondrian, but actually “The Door” came from something I saw when I was going out of a gallery in Paris one day. I noticed a wall and some structures. Someplace in my memory, I wanted to recapture the movements I had seen, which started me off on that painting. Some of my paintings begin like that, with the memory of a movement, or a dislocation of something but not all.

Rail: I’m intrigued by the relationship between your forms and things in the world. You are careful to avoid direct references, but your paintings are full of associations; they are far from pure, disembodied geometry. I’ve been thinking about this in relation to some New York painters. You’ve often been compared to Jonathan Lasker, but his work has very little sense of the visible, tactile everyday world. By contrast, I see more affinities with Amy Sillman and Carrie Moyer. Even though their paintings look nothing like yours, both of them work with shapes that are abstract yet ripe with associations, often figural.

Jaffe: I’ve seen Jonathan Lasker’s paintings in Paris, but none of Amy Sillman’s or Carrie Moyer’s.

Rail: What I’m interested in is how you think about the space between avoiding recognition and suggesting resemblances.

Jaffe: I might be sensitive to what I’m seeing outside. Mind you, I realize that I ignore people and that I avoid singularity, that I’m involved in a general congestion of events. I can be visually inspired by what I see that has that. It’s like a scenic stage set, which I reduce or try to adjust. Whether these other artists are involved with that, I don’t know. I know that I am. And I also know that I’m concerned with involving people in seeing what’s in front of them, instead of metaphysically, or philosophically. It’s something about the present that I want to force people to see. And so, when I make a picture, that’s what I’m involved with.

Rail: And if the painting can achieve that, you know it’s finished.

Jaffe: I want a certain tenseness, a congestion or a combination of forms in which none is stronger than any other. I’m interested in the idea of coexistence.

Rail: In 2007, Tibor de Nagy did a show of American painting in Paris in the 1950s. I was struck by what made your work different from everyone else’s. In your early 1950s paintings every gesture is unique. They have an incredible multiplicity, whereas most of the other artists in the show had a limited number of gestures and moves that they would reuse to create the painting. And you never repeated a mark. That, I think, is something that continued through into the nongestural work.

Jaffe: Well, that’s why my work was read differently at the time. I wanted to bring out what I thought was a particular interest of mine, and which I don’t think was visible then. Now, it might be.

Rail: Was the move from gesture to geometry a way of allowing color to have a much bigger role?

Jaffe: Intellectually, it seemed to me that it was stupid to continue making gestures to develop the painting when the gesture wasn’t pure. I was reworking a gesture, which should be beautiful in itself, and in the process what I was doing was destroying the color, because I overworked, and repeated. You know, I was destroying the essence of what we would call gesture. It was like taking a beautiful Chinese line and constantly redoing it.

Rail: In the 60s, there is more color in your paintings. It’s also a time when the urban landscape and cultural environment was becoming more brightly hued. My image of Europe in the decades immediately after the war is one of grayness. Then, in the 1960s, things get much more colorful, in advertising, in movies, in the total environment.

Jaffe: I don’t know. But, remember, 1968 took place in France. The student upheaval gave everybody a sense that we can do something else. That probably affected me.

Rail: May ’68 pretty much coincided with your full embrace of geometrical form, something you’d been moving toward throughout the 60s.

Jaffe: I was there and I remember it. There was a spirit in the air. You knew you were watching social upheaval.

Rail: And people building barricades in the street and tearing things down and re-arranging the world to suit themselves.

Jaffe: Absolutely. I think that possibly would have affected me as well.

Rail: Your work looks so different from every other American painter of your generation. The only one of your contemporaries I can think of with whom you had any formal affinity is George Sugarman, a sculptor. Were you in contact with him in the 1960s?

Jaffe: I remember George coming to see me, at some point in that period, before I really radically started with very flat surfaces. There was a period where everything coalesced; I don’t know how to put it. But George thought that I was getting into a certain kind of post-cubist painting, which he didn’t like at all. He was very frank about his assessment of what I was doing, but he was also responsible later for helping me get a show at Artists Space.

Rail: I see you and George as being mutually interested in inventing forms, and working with color and discontinuity. You both took from Matisse, and went beyond him.

Jaffe: Not beyond, but differently.

Rail: There’s a painting here, “Hop and Skip,” the one borrowed from MoMA, that is something different from every other painting in the show, and from most of the paintings you’ve done in the last 20 years.

Jaffe: And what is it?

Rail: Almost none of the shapes touch each other! Touching and not touching is something you’ve played with a lot. Sometimes you have shapes approach each other to within a millimeter, but, in general, everything is always touching. Does “Hop and Skip” belong to a period where you were working with separate shapes, or did it just happen to come out that way?

Jaffe: I think it just happened. But it makes me think of some other paintings that aren’t here, and I’d like to go look at their reproductions to see if they did that too, because that painting was part of a group that I showed at Fournier. I don’t remember which paintings were together, but I think that there probably were other paintings that had the same sensibility.

Rail: Strangely enough, it has another unusual characteristic, which is that it doesn’t have any black. There is almost always black in your paintings, somewhere.

Jaffe: I’ve done many paintings without blacks, though in recent years I’ve used blacks a lot more.

Rail: I wanted to ask you about the exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, Elles, which consists of only work by women from the museum’s collection. You have work in it.

What do you think of the show and its premise?

Jaffe: At the beginning, I thought that it wasn’t a very happy idea to only single out women. It wasn’t a militant feminist show; I didn’t really know what kind of show it would be. When I saw the show I realized that they had pulled it off, even though there were a lot of women I consider to be important artists that were not in the show, because Beaubourg had never collected them. Ultimately the show was like every group show. You didn’t say, “Oh, it’s done by a woman.” Either it’s poor or it’s weak. It was work that either you liked or didn’t like, like every other group show, and you forgot that it was only women.

Rail: I think that’s something that you would only get by actually seeing the show because, from an American perspective, it seems sort of essentialist and something that seems simplistic, a simplistic approach to the question of women artists and their representation.

Jaffe: You know, there have also been French critics of the show, asking “Why a feminist show?” and so on and so forth. But ultimately it seems to me that it’s a good example of the fact that we can criticize everything, no matter how positive. The show has been extremely well attended, which is interesting.

Rail: You have said that you want to give every shape its own space. But at the same time, there’s so much happening in the paintings, more and more all the time. It’s like a conversation in a room or lots of conversations going on at the same time, but you can hear every voice. Very different from, say, Frank Stella. He packs a lot in but doesn’t give that sense of each form having its clear, lucid space.

Jaffe: I’m involved with relationships. And remember, I don’t intend the whites or the blacks to be background shapes. I mean them to be informative, links with the so-called forms. Those intermediary forms matter.

Rail: Even when forms seem similar, they are not. I think of your great painting “Egg Nog” (1991), which has a dozen black shapes scattered around the painting and, as I remember, each black is a different black.

Jaffe: This also happens in an older painting in this show, “Four Squares Black” (1993). Each black is slightly different. You don’t see it, but this creates another resonance.

Rail: You feel it. Also the yellows in the upper right quadrant of “Four Blacks,” two different yellows right next to each other. In one interview you talked about your ongoing argument with Joan Mitchell about whether it was possible to express emotions and feelings in other ways besides gesture.

Jaffe: Joan avoided that kind of conversation. I was in the middle of churning around, wondering where do I want to go and how? I wanted to talk.

Rail: I was curious about the title of one of the new paintings, “Bande Dessinée en Noir et Blanc.”

Jaffe: There were some forms that made me think of comic strips, so I put that in the title to help me remember which picture it is. That’s how I choose titles. Sometimes they might have an intuitive relationship to the painting that has no meaning to anyone but me.

Rail: Your titles keep things open. There’s space for the viewer to go wherever he or she wants. They don’t pin down what the painting is about.

Jaffe: I have a good time, generally, finding titles.