ART WRITING

ARTICLES

LEE MILLER

Portrait of Space, Al Bulwayeb, Near Siwa, Egypt, 1937, gelatin silver print, 12 by 10¾ inches.

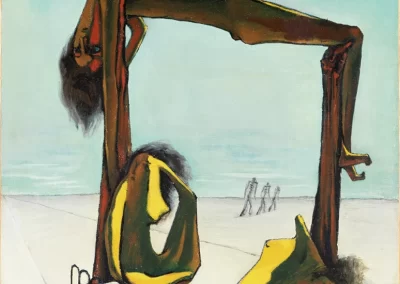

ABDEL HADI EL-GAZZAR

The Green Fool, 1951, oil on cardboard, 28¾ by 27½ inches. Collection Naguib Sawiris, Cairo

Surreal Cairo

Art in America, January 2017

By Raphael Rubinstein

A traveling exhibition brings the Surrealist paintings and drawings of Art et Liberté, an avant-garde Egyptian art group active during the Second World War, to audiences outside of their country.

NEAR THE BEGINNING of Egyptian writer Waguih Ghali’s great comic novel Beer in the Snooker Club, the narrator Ram and his friend Font indulge in their favorite beverage, or at least the Cairo version of it:

“Draught Bass, Font?”

“Yes, all right.”

I opened two bottles of Egyptian Stella beer and poured them into a large tumbler, then beat the liquid until all the gas had escaped. I then added a drop of vodka and some whisky. It was the nearest we could get to Draught Bass. 1

Set in the years before and after the 1952 revolution that overthrew King Farouk, Beer in the Snooker Club, written in English and published in 1964, brilliantly portrays privileged Cairo youth reeling from or trying to blithely ignore the social and political chaos around them. Although poor in relation to their spoiled rich friends, Ram and Font have been educated at a posh English-style school and spent four years living in London. Hence their passion for Draught Bass Ale, a libation apparently unavailable in Egypt in the 1950s. The two young men are keenly aware of their dilemma as Westernized Egyptians who nonetheless despise colonialism and its legacy of racism and underdevelopment. “The real trouble with us,” Font observes, as they drink their doctored ales, “is that we’re so English it is nauseating. We have no culture of our own.”

I was reminded of this scene from Beer in the Snooker Club as I walked through “Art et Liberté,” a revelatory exhibition currently on view at the Reina Sofía in Madrid, that I saw at Paris’s Centre Pompidou last fall. Subtitled “Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938–1948),” the show delves deeply into the history of Art et Liberté, a group of Egyptian artists, writers, and activists who espoused Surrealist-influenced ideas against the backdrop of the Second World War. Hitherto virtually unknown outside of Egypt, the Art et Liberté artists would appear to be victims of the kind of marginalization that has historically affected so-called peripheral cultural phenomena. Certainly, their absence from the Western art history canon is largely the result of European imperialism, but the show’s curators, Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, urge us to be wary of binary thinking when it comes to Art et Liberté. As Bardaouil writes in his catalogue essay, “to reduce the example of Art et Liberté to the polemics of post-colonial rhetoric seems to me in contradiction with how the group perceived itself, and ill serves it. Instead of making it the victim of a marginalizing Eurocentrism, it is preferable to highlight its role as an active catalyst in the evolution . . . of Surrealism at the time.” 2 Bardaouil and Fellrath want us to recognize the specifically Egyptian qualities of Art et Liberté and also to appreciate how the group contributed its unique perspective to Surrealism on an international scale.

While I doubt that any of the Art et Liberté participants would ever have said “we have no culture of our own” or found anything nauseating about their embrace of foreign influences, how they went about creating distinctive forms of expression isn’t so different from that of Ghali’s amateur mixologists. By adding powerful ingredients—disorienting pictorial devices, unconscious-derived imagery, a fusion of radical aesthetics and politics—from the European avant-garde to everyday Egyptian reality, Art et Liberté achieved not some weak imitation of a foreign model but an original and intoxicating concoction.

IN THE MANNER of all classic avant-gardes, Art et Liberté announced itself, in December 1938, via a manifesto: “Vive l’art dégénéré” (Long Live Degenerate Art). Issued in response to the Nazi’s 1937 Degenerate Art exhibition, and signed by nearly forty self-described “artists, writers, journalists and lawyers,” the bilingual French and Arabic pamphlet, which sported a reproduction of Picasso’s Guernica, rejected the vilification of modern art in Germany, Austria, and Italy, and the virtual resurrection of the Middle Ages “in the heart of Europe.” Although Egypt is nowhere mentioned, one sentence signals that it wasn’t only Europe that was on the minds of the signers: “Art is, by its nature, a constant intellectual and emotional exchange in which humankind as a whole participates and which cannot therefore accept such artificial limitations.” 3 Two years later, following the group’s first collective exhibition, one of its founders, poet Georges Henein, was more explicit about the international (and antireligious) character of their project: “Art has no country, no territory. Chirico is not more Italian than Delvaux is Belgian than Diego Rivera is Mexican than Tanguy is French than Max Ernst is German than Telmisany is Egyptian. All these men participate in the same fraternal impulse against which the logic of the bell tower and of the minaret can only raise a pathetic barrier.” 4

The son of an Egyptian diplomat father and an Italian-Egyptian mother, the multilingual Henein grew up in Cairo, Madrid, Rome, and Paris. In Paris, at the age of twenty-two, he met André Breton. Despite his youth, Henein quickly became the main conduit for the introduction of Surrealism into Egypt, through writing, lectures, and even a radio broadcast. Besides promoting the creation of Surrealist art and poetry, Henein sought to enlist his Cairo colleagues in the struggle Breton was waging against Stalinist orthodoxy. 5 Also key to the early development of Art et Liberté were painter (and later filmmaker) Kamel El-Telmisany, theorist and painter Ramses Younane, and two brothers, painter Fouad Kamel and writer Anwar Kamel (the latter’s recorded voice could be heard reminiscing in the show’s first gallery).

“Vive l’art dégénéré” was followed by a whirlwind of activity centered on publications launched by Henein and his colleagues, including a French and Arabic art bulletin, an Arabic-only journal titled Al-Tatawwur(Evolution) and a French-Arabic magazine, Don Quichotte. Among the many impressive aspects of this exhibition is the wealth of documentation on view—journals, books, posters, exhibition announcements, photographs—a veritable archive of the Egyptian avant-garde that couldn’t have been easy to assemble. Bardaouil and Fellrath, independent curators operating under the name Art Reoriented, with a focus on the Middle East, say they spent five years working on the exhibition. One can easily believe it, judging by the rare and fugitive printed matter on display and the large number of public and private collections, mostly in the Middle East, that loaned art to the show. Throughout the exhibition there is an emphasis on the close relations between artists and writers. One gallery at the Pompidou featured a wall with a diagramlike arrangement of framed first editions connected by lines tracking the international reach of important Cairo writers, such as Albert Cossery and Edmond Jabès, who were associated with Art et Liberté.

FOR A VIEWER unfamiliar with twentieth-century Egyptian art there are so many discoveries, so many new names, that it’s hard to know where to begin. Two of the most immediately striking artists are Inji Efflatoun and Amy Nimr. Handling thickly painted oils and a dark, rich palette that makes everything appear to be illuminated by flames, Efflatoun portrays figures in landscapes populated with threatening forms. In Jeune Fille et Monstre (Girl and Monster, 1941), a naked woman is engulfed by flames. All we see of the “monster” is an enormous clawlike hand in the foreground, but it is more than enough to convey terror, as the woman’s impossibly long black hair billows like smoke against the desert. In a larger painting of the same title from a year later, the scene has turned gruesome, presenting impaled bodies with blood seeming to drip from the sky. Nimr’s watery ink-and-gouache works of the early 1940s are lighter in feel than Efflatoun’s paintings but they, too, are suffused with death and violence, here in the form of undersea views packed with drifting human skeletons.

In a landscape full of faceless figures, corpses, and dead trees sprouting thick tresses, Samir Rafi depicts a massacre riddled with symbols as well as victims. More Expressionist than Surrealist (and with a touch of Rouault), El-Telmisany’s 1940 gouache Sans titre (blessures) (Untitled [Wounds]) is a gory picture of two entwined naked figures riven by giant spikes.

Non-allegorical violence is the subject of Coups de Bâtons (Club Blows, 1937), a memorable painting that Mayo (Antoine Malliarakis) made in response to the street protests that occurred in mid-1930s Cairo, where police and rival paramilitary youth groups were constantly clashing. Freely mixing highly abstracted figures and realistically painted objects in a pictorial melee, Coups de Bâtons falls just outside the official timeframe of the show (1938–48), as do a number of works by other artists. Born in Port Saïd to Greek and French parents, Mayo spent most of the 1920s in Paris, studying art and meeting important Surrealists such as Man Ray and Tanguy. In 1941 he left Cairo for Paris, where he worked extensively as a costume designer for film director Marcel Carné, most notably on the classic Les Enfants du Paradis (1945).

The many images of violence and of mutilated or deformed bodies—especially in a section of the exhibition titled “Fragmented Bodies”—are hardly surprising, given that most of Art et Liberté’s activities occurred against a backdrop of global war. Conflict was inescapable in Cairo, although the city was never attacked directly. As the headquarters of the British Eighth Army, the city was flooded with British soldiers and came dangerously close to falling to the Germans in late 1942. Cairo was also filled with European refugees, who amplified the cosmopolitan quality that had long characterized the city at the same time that they acted as vivid reminders of fascism’s threat to liberty.

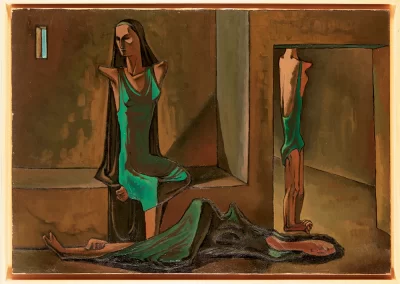

There were also subtler ways in which the war impacted the iconography of Art et Liberté. In the section of the show titled “The Woman of the City,” the curators examine how some painters depicted the prostitution that, as a result of extreme poverty and a heavy military presence, was rampant in Cairo. Refreshingly free of prurience, moral disapproval, or an oppressive male gaze, the paintings of nude women by El-Telmisany and Fouad Kamel are characterized by pathos and extreme physical deformation. A deep melancholy is conveyed in an untitled 1943 painting by Younane featuring three figures or maybe three versions of the same figure: a gaunt, armless woman who sits, stands, and melts away in a prisonlike interior. The bleakness of these paintings echoes the ambience of Cossery’s books, which recount the desperate lives of Cairo’s underclass. (Although Egypt’s 1988 Nobel Laureate Naguib Mahfouz wasn’t associated with Art et Liberté, the theme of prostitution in 1940s Cairo is central to his famous novel Midaq Alley, first published in Arabic in 1947.)

It’s not difficult to identify which European artists influenced the Art et Liberté painters: the empty spaces and long shadows one sees in paintings such as Younane’s Contre le mur (Against the Wall, 1944) recall de Chirico, while his La nature appelle le vide (Nature Calls to the Void, 1944) and an untitled 1939 canvas of an angular, impossibly elongated figure arching over a flat, empty landscape strongly suggest Tanguy, an effect one also sees in some paintings by Hassan El-Telmisani, Kamel’s younger brother. Mayo’s Coups de Bâtons suggests deep familiarity with Picasso. Also clearly in the mix were André Masson, Max Ernst, and Salvador Dalí. None of these artists appears to have shown their work in Egypt, so exposure happened through travels (many Art et Liberté artists had studied or lived abroad) and reproductions in journals such as Verve and Minotaure.

The exhibition includes one particularly fascinating instance of international influence, which not only reveals how boldly some Egyptian painters went about transforming visual ideas arriving from Europe but also provides evidence of the complex network of friendships and exchanges that nourished the Cairo avant-garde. Hanging on the wall next to Younane’s arching figure was a slightly larger painting, also dated 1939, titled Egypt and made by Roland Penrose. A British Surrealist who translated “Vive l’art dégénéré” for the London Bulletin, a Surrealist journal that he coedited, Penrose traveled to Egypt in early 1939 to be with his lover, photographer Lee Miller, who was married to a wealthy Egyptian and had been living in Cairo since 1934. (Although she left Egypt for England just as Art et Liberté was launched, Miller, through both her art and her connections, did much to strengthen the links between the Egyptian and European Surrealists; she was also one of the many women who played an important role in the movement, from artists such as Nimr and Efflatoun to Marie Cavadia-Riaz, a writer and patron whose literary salon was vital to the Cairo avant-garde.)

Borrowing from one of Penrose’s own drawings of a nude Miller on hands and knees, Egypt invites us to gaze into a darkening desert through an arched form that is part human figure, part landscape. In Younane’s painting, an emaciated female figure the color of mahogany is stretched between two postlike structures. Below her are a pair of mysterious shardlike forms out of which human faces emerge. In the distance three figures march toward a far-off horizon, as perspectival lines traverse the receding plane and wispy clouds float in a big sky. It’s a much more unsettling painting than Penrose’s, and executed with an almost cruel starkness that underlines a certain finicky, overly elegant (qualities that plague much modernist British art) aspect of Penrose’s version. The exhibition catalogue doesn’t indicate the order in which these works were created, but I suspect Penrose’s less challenging painting came first, and that Younane took the Englishman’s idea into more extreme territory.

Interestingly, there is a similar composition in one of Miller’s photographs included in the show. Carrying the elaborate title Portrait of Space, Al Bulwayeb, Near Siwa, Egypt and dated 1937, it shows a view of the desert several hundred miles west of Cairo as seen through a piece of torn mosquito netting. The upper edges of the tear create an arch over the empty desert not unlike the bodies in Penrose’s and Younane’s paintings. Continuing the chain of influence, Portrait of Space is said to have been the inspiration for René Magritte’s The Kiss (1938), in which a patch seems to have been torn out of a verdant landscape to reveal a desert domain.

The photography section of the show is as full of new names as the rest of the exhibition. Especially impressive is Ida Kar, a Russian-born Armenian whose family moved to Egypt when she was a teenager. She is represented by some weird still-life images (most notably a close-up photo of a cloth doll and a carved Pharonic head) and photomontages made in collaboration with Angelo de Riz, an Italian anarchist. (During the war, Kar met and married Victor Musgrave, an Englishman serving in Egypt with the Royal Air Force. Musgrave became a prominent art dealer in postwar London, where Kar continued her photography practice, specializing in portraits of artists.) Egyptian photographers Mohammad Abdel Latif, Ramzi Zolqomah, and Ahmed Sawwan experimented with photomontage and solarization. Images of the pyramids show up repeatedly in the exhibition, usually from disorienting perspectives.

NO ONE, even among Egypt’s privileged class, was spared the effect of war. One day in 1943, Nimr, born in Cairo to a Syrian newspaper magnate and an English mother, and married to a British diplomat, went with her family for a desert picnic. While she and her husband were resting, their eight-year-old son wandered away and picked up what turned out to be an unexploded bomb. It went off, killing him. This tragic incident was to inspire an episode in a novel by Olivia Manning, one of the numerous British writers who ended up in Egypt during the war, either seeking refuge or serving with the armed forces. They included Lawrence Durrell, who also drew on Nimr’s life for his Alexandria Quartet, and numerous poets. Because the Art et Liberté artists were closer aesthetically, politically, and culturally to France than to England, and because they resented the sway that Great Britain held over Egypt, their exchanges with British writers never approached the intensity of their dialogue with the Parisian Surrealists. Nonetheless, there were significant Anglo-Egyptian dialogues, among them one of the most extensive examples of literary-artistic collaboration in the show: fourteen delicate ink-and-colored-pencil drawings by Eric de Nemes illustrating an unpublished war-themed poem by British poet John Waller. A Hungarian illustrator who came to Egypt via Beirut, Nemes was one of many displaced Europeans who contributed to Cairo’s artistic vitality. 6

In a section of the show titled “Writing with Pictures,” the curators emphasize the close bonds between artists and writers in 1940s Cairo. On display were books by Henein and Cossery, with illustrations by Kamel El-Telmisany; an English translation of Cossery’s book of short stories The Men God Forgot (published in 1944 by Circle Editions, an anarchist press in Berkeley, California), for which Younane contributed a striking cover drawing (through Durrell’s friendship with Henry Miller, there was a Cairo-California connection); and a copy of Jabès’s early volume of poetry Les Pieds en l’air (Feet in the Air), illustrated by Mayo. Also on display were all the chapbooks published by Jabès and Henein’s small press, La Part du Sable, a treat for devotees of Francophone Egyptian literature.

As the war ended, conditions became less favorable for Art et Liberté, leading to its dissolution in 1947. Two years before, one of its key members, El-Telmisany, had already abandoned painting for film. Suspicious of the group’s political activities and writings, the Egyptian government began arresting some of its members, including Younane, who after being briefly jailed in 1947 left for France. (It was during Younane’s incarceration that the group disbanded.) That same year a number of younger artists, several of whom had been included in Art et Liberté’s exhibitions, formed Le Groupe de l’Art Contemporain, which sought to incorporate more identifiably Egyptian elements into its work. For some of the Art et Liberté founders, this looked too much like a new form of nationalism, something they had been against from the beginning. The curators underline these internecine arguments by including, among the wall texts, excerpts from a highly critical letter Henein wrote to Younane in the 1950s accusing the younger painters of being spokesmen for “new fascists in uniform,” by which he meant the postrevolutionary Nasser government. To my eye the strongest of these painters, too many of whom surrender to sentimentality and cliché, is Abdel Hadi El-Gazzar, whose late 1940s and early 1950s works, such as Incantation (1948) and Le Fou Vert (The Green Fool, 1951), feature boldly colored Fellini-esque scenes thronging with symbols drawn from Egyptian superstition and folklore. There is an intriguing debate around the issue of nationalism in El-Gazzar’s later work. Initially seen as a celebration of Nasser’s policies, allegorical paintings such as The Charter (1962) now appear to some scholars as encoded with subtle critiques of post-1952 Egypt.

ALTHOUGH THE Art et Liberté artists and writers had long been contending with a repressive monarchy (group members were frequently jailed in the late 1940s), the 1952 revolution that brought Nasser to power eventually drove many of them into exile. 7 As a result, the 1950s proved to be a damaging decade for Egyptian culture, and for the cosmopolitan atmosphere that had long marked Cairo and Alexandria. In 1956, in the wake of the Suez Crisis, much of Egypt’s long-established Jewish community was forced out of the country—including Jabès, who lived the rest of his life in Paris. 8 That year also saw the departure of patron Marie Cavadia-Riaz, whose salon had been at the core of Cairene artistic life since the 1930s. Nimr likewise left in 1956. Henein held on until 1960, when he and his wife departed for Europe. Although Efflatoun remained in Egypt until the end of her life, the Nasser government imprisoned her for four years because of her leftist activism.

The fact that it has taken this long for a European art museum to pay serious attention to Art et Liberté may have as much to do with the lack of appreciation shown them in Egypt as with any Eurocentric bias. For a long time, and perhaps even now, the international character of Art et Liberté damned it in the eyes of some nationalistic Egyptians, who may also have been troubled by its religious inclusivity. As art historian Don Lacoss observes in the catalogue, the members of Art et Liberté were “Muslims (Sunni and Shiite), Jews and Christians (Coptic and Protestant) . . . but religion was a private affair that the group as a whole does not seem to have discussed.” 9 At once long overdue and extremely timely, this exhibition is part of the ongoing globalization of modern art history; it also occurs within the specific context of recent developments in the Middle East, from the tragically derailed Arab Spring (especially affecting Egypt) to the explosive growth of art collecting, public and private, in the Persian Gulf region, to say nothing of the horrors of violent fundamentalism and the rampant Islamophobia in Europe and North America. Bardaouil and Fellrath are keenly aware of the larger issues raised by their exhibition. For them, Art et Liberté offers a model to counter the excessively binary and essentialist arguments, epitomized by Edward Saïd’s analysis of Orientalism, that pit West against East. Rejecting Saïdian dualism because it risks reducing non-Western subjects to “passive victims,” Bardaouil, in his introductory essay, points instead to Zygmunt Bauman’s “liquid modernity,” Aimé Césaire’s “creolization,” and Benedict Anderson’s concept of “imagined communities.” It is common today for curators to make grand theoretical claims for their exhibitions, and just as common for their shows to fail to live up to the inflated rhetoric that surrounds them. How welcome, then, to encounter an exhibition rich and complex enough to sustain its ambitious intellectual framework, and even to go beyond it. Potent stuff, that Draught Bass.

CURRENTLY ON VIEW “Art et Liberté: Rupture, War and Surrealism in Egypt (1938–1948),” at the Museu Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, Madrid, Feb. 14–May 28. The show travels to Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf, July 15-Oct. 15.

Endnotes

1. Waguih Ghali, Beer in the Snooker Club, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1964, p. 17.

2. Sam Bardaouil, “Le Group Art et Liberté et la Refondation du Surréalisme en Égypte (1938–1948),” in Art et Liberté: Rupture, Guerre et Surréalisme en Égypte (1938–1948), ed. Sam Bardaouil and Till Fellrath, Centre Pompidou, Paris, 2016, p. 17. Unless otherwise noted, all translations from French are by the author.

3. “Long Live Degenerate Art,” London Bulletin 13, 1939, translated by Roland Penrose, reprinted in Black, Brown & Beige: Surrealist Writings from Africa and the Diaspora, ed. Franklin Rosemont and Robin D.G. Kelley, Austin, University of Texas Press, 2009, p. 148.

4. Georges Henein, “L’Art en Egypte (X): El-Telmisany,” Don Quichotte, no. 17, March 29, 1940. Quoted in Patrick Kane, The Politics of Art in Modern Egypt: Aesthetics, Ideology and Nation-Building, London, New York, I.B. Tauris, 2012, p. 202, n. 51.

5. In fact, the name Art et Liberté was inspired by “Manifesto for an Independent Revolutionary Art,” a polemic that was published earlier in 1938 and signed by Breton and Diego Rivera, though it had actually been written by Breton and Leon Trotsky during Breton’s sojourn in Mexico. Henein’s plan was that Art et Liberté would play an active role in the Fédération Internationale de l’Art Révolutionnaire Indépendant, the short-lived movement that Breton and Trotsky hoped would attract anti-fascist and anti-Stalinist artists from around the world.

6. Apparently Cairo suited Nemes: he was still living there in the early 1960s, when Maya Angelou encountered him while both were working for the Arab Observer, an English language news magazine. In her memoir, The Heart of a Woman, she recalls him as a lay-out artist who “showed me that where an article was placed on a page, its typeface, even the color of ink, were as important as the best-written copy.” Maya Angelou, The Heart of a Woman, New York, Random House, 1981, p. 289.

7. An early exile was Albert Cossery, who left for France as soon as the war ended. Although he lived the rest of his life in Paris, his books were invariably set in Egypt or other North African locations.

8. In the decade preceding his departure for France, Jabès had already been distancing himself from Art et Liberté, and Surrealism in general. In a book of conversations with Marcel Cohen, he explained why: “After the war, if I still had even the slightest desire to adhere to Surrealism, I would have been prevented from doing so by an exhibition organized in Cairo, in 1947, by the Egyptian Surrealist group, echoing the one that had just happened in Paris. There one saw, among other things, tailors’ mannequins disemboweled with knives and stained with red ink, right after we had discovered all the horror of the camps. It seemed to me that this was an unacceptable indecency.” Edmond Jabès, Du Désert au Livre: Entretiens avec Marcel Cohen, Pessac, Éditions Opales, 2001, p. 40. I have been unable to find documentation, photographic or otherwise, of the art installation that outraged Jabès.

9. Don Lacoss, “Surréalisme Égyptienne et Art Dégénéré en 1939,” in Art et Liberté, p. 233.